H-1B VISAS: A HIGH-TECH DILEMMA

INTRODUCING THE DEBATE

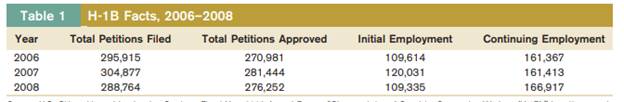

The public face of the immigration debate in the United States has typically revolved around illegal workers filling low-wage/low-skill jobs. Traditional wisdom dictates that some work is so labor-intensive and poorly compensated that it can only be performed by desperate foreigners with limited options. However, there is another aspect of the immigration debate that generates no less controversy but receives far less public scrutiny. The H1B temporary worker visa program has long been a thorn in the side of U.S. companies looking to attract highly skilled foreign labor. The high-tech industry has been particularly impacted and has sought to liberalize the rules and regulations governing H-1B. Opponents of the program have characterized its current form as the present-day version of indentured servitude. Some domestic labor groups have argued that temporary workers are an unnecessary evil that depresses wages and takes American jobs away from Americans. The H-1B is a visa program that allows foreign individuals with highly specialized knowledge and skills to work in the United States for a maximum of six years. It was initiated in the 1950s to attract mathematicians, physicists, and engineers from behind the Iron Curtain. H1-B has undergone many revisions since its inception. However, it has not been able to keep pace with the changing needs of American employers. This is best illustrated by the information technology sector, where historically robust labor demand is projected to grow by approximately 40 percent by 2016. The industry’s growth long ago outpaced the domestic supply of skilled workers, leaving IT companies to navigate the murky waters of securing H-1B visas for qualified foreigners. Keeping up with legislative changes to the program is a full-time job in itself. In 2000, Congress approved a three-year increase in the H-1B allotment from 115,000 to 195,000. The bill passed, largely because high-tech lobbyists were successful in positioning the visas as protection for the U.S. competitive edge in technology. However, when the three years were up, the allotment was scaled back drastically under pressure from domestic interest groups, using the dot-com bubble burst and resulting temporary sector contraction as partial justification. Currently, there are only 65,000 H1-B visas available, with an additional 20,000 reserved for foreign holders of U.S. advanced degrees. That number’s inadequacy is plainly obvious, when one considers that for the 2008 tranche, there were 123,480 applications filed in the first two days after the offer date. The Bureau of Citizenship and Immigration Services resorted to a lottery to determine who would get a visa and who would not. As Table 1 demonstrates, demand for H1-B visas has long outpaced supply. Do note that the data includes visas given to employers exempt from the cap, such as colleges, universities, and nonprofit research organizations. It is plainly obvious that even amidst a global downturn, the program has not been able to accommodate demand both from American employers and willing immigrants. This limits the country’s human capital growth and, consequently, its productivity and overall economic expansion. Experts predict that as the economy rebounds, demand for H-1B visas will spike, further exposing the program’s inadequacies. Simultaneously, growing domestic concerns over unemployment, irrespective of the uneven distribution of job losses across sectors, have led to accusations of H-1B abuses and calls for increased oversight and more stringent controls. In response to these political pressures, Congress passed a measure in February of 2009, limiting the use of H-1B visas by financial firms that have received bailouts. The mainstream media response was largely negative. The Washington Post characterized the provision as ‘‘antithetical to innovation and domestic prosperity.’’ The Wall Street Journal published a critical editorial, titled ‘‘Turning Away Talent,’’ and New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman called it ‘‘S-T-U-P-I-D.’’ However, it is important to recognize that the labor market has indeed managed to find ways of circumventing the stringent H-1B regulations. For example, use of L-1 visas, or short-term visas for intra-company transfer increased by 34 percent from 2004 (62,700) to 2008 (84,078). Such visas have no annual cap and no requirement to pay holders the prevalent wage, and hence companies find them less politically sensitive and more userfriendly. However, they make it hard to retain the best and the brightest, since L-1s represent only a temporary

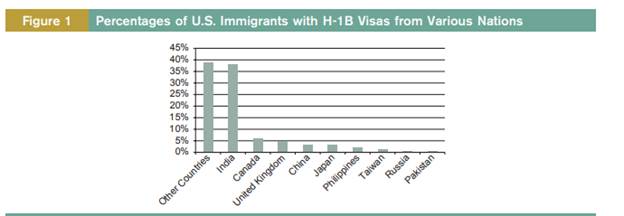

fix. There also are some flagrant abuses of the system, exemplified by one company that filed numerous H-1B petitions for Iowa, where prevalent wages are lower than the national average, and then transferred approved workers to higher-wage areas. THE CRITIC’S POSITION Examples, such as the one above, provide justification for interest groups that seek a complete overhaul of the H-1B system. Their main grievance is that employers are not required by law to demonstrate a shortage of U.S. workers in their field. They point to the Labor Department’s 2006–2011 Strategic Plan, which states that ‘‘H1B workers may be hired even when a qualified U.S. worker wants the job, and a U.S. worker can be displaced from the job in favor of the foreign worker.’’ This critique is predicated on the assumption that employers exaggerate labor shortages in order to hire cheaper workers from abroad. There are some numbers to support such claims. The median annual wage for new H-1B holders in the IT industry, including those with advanced degrees and years of experience, was $50,000 in 2005 (the last year for which USCIS provided such demographic statistics). Simultaneously, entry-level U.S. workers with only a bachelor’s degree in the field made, on average, $51,000. However, even if this line of argument is correct in the majority of cases, basic economic theory would suggest that the macroeconomic effects might actually be beneficial. The H1-B program is designed to increase the supply of skilled workers, and hence reduces wages for the most affected occupations. Companies are able to secure lower paid labor, which reduces costs and increases the overall economy’s profit potential. This argument has been previously used for using cheaper imports in the textile and steel industries, which have translated into lower consumer prices and economic expansion. In other words, increasing America’s knowledge base and stock of human capital would escalate long term growth and the earning potential of all workers. Other critics question whether H-1B attracts the best and the brightest. They argue that truly exceptional workers constitute the minority of the visa holders and point out that the minimum degree requirements for H1B are rather low—a bachelor’s or equivalent experience. The implication is that H-1B is becoming obsolete, given that there are plenty of capable Americans, eager and willing to work, especially in the wake of the global economic collapse and rising unemployment rates. However, this criticism does not take into account long-term processes or current and future differences in labor supply and demand across industries. There are some key economic and demographic trends that need to be considered, chief among them, the rapidly aging American workforce. The U.S. Census projects that the number of Americans 65 and older will increase by 26 percent in the next five years, while the 25 to 39 age group will grow by only 6 percent. One example of the potential impact of an aging workforce is the healthcare industry, which is already grappling with persistent labor shortages. The average nurse in the United States is 42 years old. Once the baby-boomers retire, replacing them will be difficult without the help of qualified foreign workers. Another important concern is the decline in domestic workforce readiness, as graduation rates for the nation’s colleges and universities have been steadily declining. In 2002, 51 percent of college students graduated within five years of initial enrollment, compared to a rate of 55 percent in 1988. Analysts are predicting that the next decade will result in a 33 percent shortfall in graduates of four-year or higher degree programs. A recent Harvard study has identified the main reason for the increasing wage gap as the sharp decline in the growth of U.S.-born skilled labor since 1980, driven by a slowdown in the rise of educational attainment levels. College-age students in the United States are faced with the double-whammy of rising tuition rates and contracting credit. Of those who do pursue higher education, fewer are entering ‘‘hard’’ science and technology-oriented tracks. For example, enrollment in key courses for computer majors has dropped by 10 to 30 percent since 2001. Simultaneously, the American economy is gradually shifting away from manufacturing and toward services, as exemplified by the ever-expanding technology sector. This trend will increase demand for science, math, and computer skills, which are in increasingly short supply. What would happen if technology companies were unable to find enough skilled workers domestically, either by using local talent or importing from abroad? In a word—outsourcing. Expediting the move of America’s technology sector overseas is not a desirable outcome, especially from a political point of view. Some policymakers have proposed a comprehensive approach to permanent skilled immigration, similar to the merit-based point systems of Canada and the United Kingdom. This could ensure expedited processing for potential immigrant workers in needed occupations. However, because of pressures from domestic interest groups, the political will for such a comprehensive overhaul has remained in short supply. THE VISA HOLDER’S PERSPECTIVE A political solution to the skilled labor and immigration debate is crucially important. However, many analysts operate under the mistaken assumption of ‘‘if you build it, they will come.’’ In other words, there will never be a shortage of highly skilled employees, willing to move to America, so immigration reform is not pressing. The incentives for international labor mobility are wellestablished and straightforward—better wages and standard of living, coupled with job security and possibilities for career advancement. From the immigrant’s perspective, the H1-B system fails on almost all counts. The visa represents a temporary work permit, held by the employer and not by the worker. Because the number of available foreign workers has traditionally exceeded the H1-B allotment (refer to Table 1), employment-based green card holders have little bargaining power with their employers and can be stuck in a less-than-ideal job for as long as ten years, with no possibility to switch companies or get a promotion. As previously discussed, they are also paid less than their American counterparts, irrespective of experience and educational attainment. At the same time, developing countries like China, India, and South Korea have implemented policies aimed at fostering return migration and retaining domestic talent. They have made massive investments in innovation, infrastructure, and R&D (research and development), with some measurable results. According to a 2009 report by the Kauffman Foundation, 50,000 highly skilled immigrants have left the United States in the past two decades for China and India. These two countries coincidentally account for the majority of H1- B visa holders (see Figure 1); 100,000 more are predicted to make the return trip over the next five years, so the trend is gathering momentum. A survey of 1,203 Indian and Chinese workers who had studied or worked in the United States for a year or more before returning home cited growing demand for their skills and lucrative career opportunities back home as the primary motivator for repatriation. Most of these individuals were in their early 30s and nearly 90 percent had master’s or doctoral degrees. Beyond returning home, in-demand workers also have more opportunities to move to developed countries other than the United States Over the past decade, many OECD [Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development] governments have recognized the looming global demographic and skill redistribution trends and have stepped up efforts to attract skilled foreign employees. For example, Germany has implemented a special visa/incentive program for information

technology workers, while Australia and Ireland have adopted fast-track work authorization for in-demand professions. The skilled workers of the future are likely to truly have the world as their oyster, with lucrative employment opportunities across the globe.

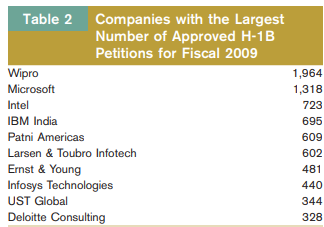

THE BALANCE In order to meet the growing needs of many of its industries, such as information technology and healthcare, the United States would have to completely reevaluate its immigration philosophy. Similar to the ‘‘Arms Race’’ and ‘‘Space Race’’ of the not-so-distant past, the global economic future likely holds an equally challenging and important ‘‘Brain Race.’’ The ability to attract and retain skilled foreign workers in key developing industries should not be taken for granted but fostered through functional immigration policies and incentives. The current H1-B system provides a temporary and imperfect fix (Table 2). On the domestic front, the knowledge base needs to be expanded through increased investment in education and industry-specific career development. Some have suggested that the market might evolve its own measures to combat employment shortages. ‘‘Microsoft University’’ and ‘‘Comcast Institute of Technology’’ could well be part of the future American academic community. However, without a comprehensive plan to restructure America’s workforce, such piecemeal solutions will not guarantee continued economic expansion and prosperity. Questions for Discussion

1. Comment on the following statement: ‘‘The firms of the New Economy seem to be awfully fond of the Old Economy of 200 years ago, when indentured servitude was in vogue.’’

2. Identify some measures that could attract American college students to the technology and ‘‘hard sciences’’ fields. Should companies in these industries bear a greater responsibility for expanding the knowledge base and reinvesting some of their profits in, for example, scholarships and loan repayment programs?

3. Should the cap for H-1B visas be eliminated altogether? Should no such provision exist at all and efforts be directed at domestic supply?