CASE

WHEN DIAMONDS WEEP

The ancient Greeks called diamonds the tears of the gods. Today, we know that natural diamonds consist of highly compressed carbon molecules. They have become a symbol of beauty, power, wealth, and love. Nevertheless, diamonds and the diamond trade are plagued by a sad reality: the exploitation of populations for diamond extraction and the use of diamond profits to fund terrorist activity and rebel groups. Trade in diamonds is highly profitable. They are readily convertible to cash, small and easily transportable, not detectable by dogs, nor do they set off metal detectors. Unfortunately, these virtues also make them an easy target for money laundering activities by terrorist and rebel groups. In addition, their high value encourages some diamond-producing countries to employ means of extraction which may violate human rights. Consider the case in Botswana where a rich diamond deposit was discovered on the land belonging to a tribal group, the Bushmen. The government forcibly resettled the 2,500 Bushmen.

THE DIAMOND PRODUCTION PROCESS: FROM MINE TO MARKET

Diamonds are mined in several different ways: from open pits, underground, in alluvial mines (mines located in ancient creek beds where diamonds were deposited by streams), and coastal and marine mines. Despite advances in technology, diamond excavation remains a labor intensive process in most areas of the world. Over 156 million carats of diamonds are mined annually (one carat is the equivalent of 0.2 grams). Once diamonds have been excavated, they are sorted, by hand, into grades. While there are thousands of categories and subcategories based on the size, quality, color, and shape of the diamonds, there are two broad categories of diamonds—gem-grade and industrial-grade. On average, close to 60 percent of the annual production is of ![]() . In addition to jewelry, gem-quality stones are used for collections, exhibits, and decorative art objects. Industrial diamonds, because of their hardness and abrasive qualities, are often used in the medical field, in space programs, and for diamond tools. After the diamonds have been sorted, they are transported to one of the world’s four main diamond trading centers—Antwerp, Belgium (which is the largest), New York, United States; Tel Aviv, Israel; and Mumbai, India. Daily, between 5 and 10 million individual stones pass through the Antwerp trading center. After they have been purchased, the diamonds are sent off to be cut, polished, and/or otherwise processed. Five countries currently dominate the diamond processing industry— India, which is the largest (processing 9 out of every 10 diamonds); Israel; Belgium; Thailand; and the United States, with China emerging as a new processing center. Finally, the polished diamonds are sold by manufacturers, brokers, and dealers to importers and wholesalers all over the world, who in turn, sell to retailers. The total timeframe from the time of extraction to the time at which the diamond is sold to the end consumer is called the ‘‘pipeline’’ and usually takes about two years.

. In addition to jewelry, gem-quality stones are used for collections, exhibits, and decorative art objects. Industrial diamonds, because of their hardness and abrasive qualities, are often used in the medical field, in space programs, and for diamond tools. After the diamonds have been sorted, they are transported to one of the world’s four main diamond trading centers—Antwerp, Belgium (which is the largest), New York, United States; Tel Aviv, Israel; and Mumbai, India. Daily, between 5 and 10 million individual stones pass through the Antwerp trading center. After they have been purchased, the diamonds are sent off to be cut, polished, and/or otherwise processed. Five countries currently dominate the diamond processing industry— India, which is the largest (processing 9 out of every 10 diamonds); Israel; Belgium; Thailand; and the United States, with China emerging as a new processing center. Finally, the polished diamonds are sold by manufacturers, brokers, and dealers to importers and wholesalers all over the world, who in turn, sell to retailers. The total timeframe from the time of extraction to the time at which the diamond is sold to the end consumer is called the ‘‘pipeline’’ and usually takes about two years.

THE NOT SO DAZZLING SIDE OF THE DIAMOND TRADE

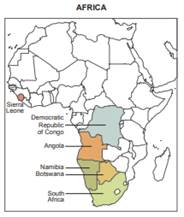

While women across the world may hope for a diamond on their finger, the industry’s sparkling reputation has been tarnished. Reports have shown that profits from the diamond trade have financed deadly conflicts in African nations such as Angola, Sierra Leone, Congo, ![]() d’Ivoire, and Liberia. In addition, reports by the Washington Post and Global Witness, a key organization in

d’Ivoire, and Liberia. In addition, reports by the Washington Post and Global Witness, a key organization in

monitoring the global diamond trade, revealed that Al Qaeda used smuggled diamonds from Sierra Leone, most likely obtained via Liberia, to fund its terrorist activities. Diamonds that have been obtained in regions of the world plagued by war and violence have thus been nicknamed ‘‘conflict diamonds’’ or ‘‘blood diamonds.’’ The use of diamonds for illicit activities has been widespread. During the Bush War of Angola in 1992, Jonas Savimbi the head of a rebel movement called UNITA (National Union for the Total Independence of Angola), extended his organization into the vast diamond fields of Angola. In less than one year, UNITA’s diamond smuggling network became the largest in the world—netting hundreds of millions of dollars a year with which it purchased weapons. Diamonds were also a useful tool for buying friends and supporters and could be used as a means for stockpiling wealth. Soon warring groups in other countries such as Sierra Leone, Liberia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo adopted the same strategy. For example, the RUF (Revolutionary United Front) in Sierra Leone, a group that achieved international notoriety for hacking off the arms and legs of civilians and abducting thousands of children and forcing them to fight as soldiers, controlled the country’s alluvial diamond fields. According to current diamond industry estimates, conflict diamonds make up between 2 and 4 percent of the annual global production of diamonds. However, human rights advocates disagree with that number. They argue that up to 20 percent of all diamonds on the market could be conflict diamonds.

THE KIMBERLEY PROCESS

Diamonds are generally judged on the ‘‘Four Cs’’: cut, carat, color, and clarity; the international community has recently pushed for the addition of a ‘‘fifth C’’: conflict. On November 5, 2002, representatives from 52 countries along with mining executives, diamond dealers, and members from advocacy groups met in Interlaken, Switzerland to sign an agreement that they hoped would eliminate conflict diamonds from international trade. The agreement was called the Kimberley Process and took effect on January 1, 2003. The Kimberley Process is a United Nations-backed certification plan created to ensure that only legally mined rough diamonds, untainted by conflicts, reach established markets around the world. According to the plan, all rough diamonds passing through or into a participating country must be transported in sealed, tamper-proof containers and accompanied by a government issued certificate guaranteeing the container’s contents and origin. Customs officials in importing countries are required to certify that the containers have not been tampered with and are instructed to seize all diamonds that do not meet the requirements. The agreement also stipulates that only those countries that subscribe to the new rules will be able to trade legally in rough diamonds. Countries that break the rules will be suspended and their diamond trading privileges will be revoked. Furthermore, individual diamond traders who disobey the rules will be subject to punishment under the laws of their own countries.

CRITICS SPEAK OUT

Several advocacy groups have voiced concerns that the Kimberley Process remains open to abuse and that it will not be enough to stop the flow of conflict diamonds. Many worry that bribery and forgery are inevitable and that corrupt governments officials will render the scheme inoperable. Furthermore, even those diamonds with certified histories attached may not be trustworthy. Alex Yearsley of Global Witness, an advocacy group trying to raise global awareness about conflict diamonds, predicts that firms will ‘‘be a bit more careful with their invoices’’ as a result of the implementation of the Kimberley Process, but warns, ‘‘if you’re determined, you can get around this process.’’ A 2005 report published by Global Witness highlighted shortcomings of the Kimberley Process and made specific recommendations for its improvement. For example, the report urges governments to implement stricter policies of internal control, advocates for the diamond industry to publicize names of individuals in companies found to be involved in the conflict trade, and pushes for the United Nations to consider implementing sanctions against diamonds from C^ote d’Ivoire. The General Accountability Office, the investigative arm of the U.S. Congress, also voiced concerns in a report: ‘‘[T]he period after rough diamonds enter the first foreign port until the final point of sale is covered by a system of voluntary industry participation and self-regulated monitoring and enforcement. These and other shortcomings provide significant challenges in creating an effective scheme to deter trade in conflict diamonds.’’ Government organizations and policy groups are not the only ones bringing the problem of conflict diamonds to light. Rapper Kanye West released a song entitled ‘‘Diamonds from Sierra Leone’’ after hearing about the atrocities of conflict diamonds in Africa. ‘‘This ain’t Vietnam still/People lose hands, legs, arms for real,’’ he raps. A Hollywood movie, The Blood Diamond, starring Leonardo DiCaprio, also features an ethical dilemma about buying and trading diamonds.

THE DIAMOND INDUSTRY REACTS Recently, a number of new technologies have emerged that, if adopted by the diamond industry worldwide, could change the way that diamonds are produced, traded, and sold. Several U.S. companies, using machines produced by Russian scientists, have been able to make industrial and gem-grade diamonds artificially. In terms of industrial-grade diamonds, which comprise at least 40 percent of all annual diamond production, this could mean tremendous cost savings for industries using industrial diamonds and the elimination of conflict diamonds from industrial uses. For gem-grade diamonds the viability of synthetic diamonds is questionable. This is largely due to the success of past diamond marketing campaigns—most consumers see synthetic diamonds as inferior to natural ones. Another emerging technology is laser engraving. Lasers make it possible to mark diamonds—either in their rough or cut stage—with a symbol, number, or bar code that can help to permanently identify that diamond. Companies that adopt the technology have an interesting marketing opportunity to create diamond brands. For example, Intel, a manufacturer of computer chips, launched a mass marketing campaign ‘‘Intel Inside’’ to create brand awareness in the previously homogenous computer chip market. While consumers don’t buy the chips directly, they have positive associations with computers using Intel chips—they may even only consider computers who have ‘‘Intel inside.’’ Likewise, establishing brand awareness and building equity in its name could add value to the diamond and help increase consumer confidence. Sirius Diamonds, a Vancouver-based cutting and polishing company, now microscopically laser engraves a polar bear logo and an identification number on each gem it processes. Another company, 3Beams Technologies of the United States, is currently working on a system to embed a bar code inside a diamond (as opposed to on its surface) that would make it much more difficult to remove. Another option is the ‘‘invisible fingerprint’’ invented by a Canadian security company called ![]() . The technology works by electronically placing an invisible information package on each stone. The fingerprint can include any information that the producer desires such as the mine source and production date. The data can only be read by

. The technology works by electronically placing an invisible information package on each stone. The fingerprint can include any information that the producer desires such as the mine source and production date. The data can only be read by ![]() own scanners. Unfortunately, if the diamond is re-cut, the fingerprint will be lost, although it can be reapplied at any time. Though this represents a major drawback of the technology, the re-cutting of a diamond is expensive and typically reduces its size and value. Nevertheless, the technology’s creators believe that it will soon become an industry standard because it is a quick and cost-effective away to analyze a stone. The technology may supplement or even replace paper certification. Lastly, processes are being developed to read a diamond’s internal fingerprint—its unique diamond sparkle and combination of impurities. The machine used to do this is called a Laser Raman Spectroscope (LRS). A worldwide database could identify a diamond’s origin and track its journey from the mine to end-consumer. However, creation of such a database requires large investments for equipment to cope with the volume of diamonds. Such investment will only happen if customers are willing to pay for such identification.

own scanners. Unfortunately, if the diamond is re-cut, the fingerprint will be lost, although it can be reapplied at any time. Though this represents a major drawback of the technology, the re-cutting of a diamond is expensive and typically reduces its size and value. Nevertheless, the technology’s creators believe that it will soon become an industry standard because it is a quick and cost-effective away to analyze a stone. The technology may supplement or even replace paper certification. Lastly, processes are being developed to read a diamond’s internal fingerprint—its unique diamond sparkle and combination of impurities. The machine used to do this is called a Laser Raman Spectroscope (LRS). A worldwide database could identify a diamond’s origin and track its journey from the mine to end-consumer. However, creation of such a database requires large investments for equipment to cope with the volume of diamonds. Such investment will only happen if customers are willing to pay for such identification.

Questions for Discussion

1. In light of the conflict diamond issue, would you buy a diamond? Why or why not?

2. Do you think the diamond industry as a whole has an ethical responsibility to combat the illicit trade in diamonds?

3. What actions, if any, should the international community take towards nations or corporations found to be trading conflict diamonds?