CASE

THE BANANA WARS

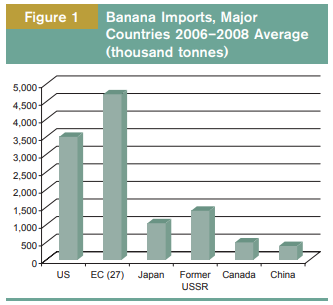

The European Union (EU) is the main market in the world for bananas, constituting 33.3 percent of all world trade (see Figure 1). That is why a decision by the EU Farm Council in December of 1992 attracted attention among bananaproducing nations. Up until the decision, different EU countries had different policies regarding imports of bananas. While Germany, for example, had no restrictions at all, countries such as the United Kingdom, France, and Spain restricted their imports to favor those from their current and former African, Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP) colonies. (This preferential trading agreement is known as the Lome Convention.) The decision called for a quota of 2.2 million tons with a 20 percent tariff for all banana imports from Latin America ($126 per ton), rising to 170 percent for quantities over that limit ($1,150 per ton). Because Latin American exports to Europe were approximately 2.7 million tons in 1992, the quota has effectively cut almost 25 percent of the countries’ exports to the EU. The main stated reason for imposing the quota and the tariffs is to protect former colonies by allowing them

to enjoy preferential access to the EU market. Other reasons implied have been the $300 million in tariff revenue resulting from the measures, as well as moving against the ‘‘banana dollar’’ (reference to the U.S. control of the Latin American banana trade through its multinationals). Belgium, Germany, and Holland have objected to the measures not only because of the preference given to higher-cost, lower-quality bananas from current and former colonies, but also because of the economic impact. The Belgians estimated an immediate loss of 500 jobs in their port cities, which traditionally have handled substantial amounts of Latin American banana imports. Twice, the European Court of Justice has rejected Germany’s challenge to the EU’s banana policy. Even in the United Kingdom, where the preferential treatment has enjoyed widespread support, there has been criticism of the decision. On two separate occasions in 1993 and 1994 panels of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) found EU banana rules to be unfair and tried to convince the EU to reform its discriminatory and burdensome banana rules. As a result of the EU’s failure to do anything, a case was initiated with GATT’s successor, the World Trade Organization (WTO), in 1996. The WTO agreed in 1997 with the complaint and turned down a subsequent EU appeal later in the same year. In 1999, the WTO authorized the United States to impose $191.4 million in trade sanctions on the EU. The last WTO ruling, again upholding the complaint, was issued in early 2008. Trade ministers tried, and failed, to secure a deal as part of the Doha Round of trade talks. Finally, the four groups involved found common ground in a separate deal. Delegates from the EU, United States, former EU colonies, and the Latin American banana powers met in Geneva more than 100 times for a total of 400 hours of talks. The settlement means less-expensive bananas for Europeans, more profit for U.S. fruit companies, and lower revenue for some former EU colonies. The EU will reduce tariffs on bananas from Latin American countries to $167 a ton in 2017 from $252 today, in return for Latin American countries dropping their WTO case. The EU’s former colonies will

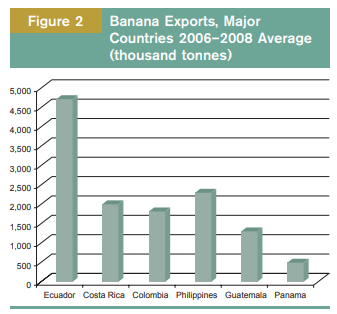

continue to receive virtually tariff-free access for its EU banana shipments, and will get a one-time cash payment of $300 million. Ecuador, the world’s largest banana exporter, hailed the deal as a victory for all Latin American nations (see Figure 2).

HISTORY OF THE BANANA

Bananas can be traced back thousands of years to ancient manuscripts by the Chinese and Arabs. European experience starts in 327 BC with Alexander the Great’s conquest of India. Bananas were introduced to the Americas by Spanish explorers in 1516. From that point on, many tropical regions with average temperatures of 80F (25C) and annual rainfall of 78 to 98 inches (2,300 to 2,900 mm) have benefited from bananas as a source of food and, increasingly, trade. Trade in bananas started only in earnest with the introduction of the steam engine and refrigeration, enabling quicker transportation and arrival in better condition to Europe and North America. As late as the Victorian era, bananas were not widely known in Europe, although they were available via merchant trade. Consumers in the United States were first introduced to bananas at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876. In the early twentieth century, bananas began forming the basis of large commercial empires, for example, by the United Fruit Company, which created immense banana plantations especially in Central and South America. The Latin American Position Bananas are the world’s most-traded fruit, and the $14.6 million tons (2008) in banana trade make it second only to coffee among foodstuffs. For countries such as Ecuador, Costa Rica, Colombia, and Honduras, the restrictions would cost $1 billion in revenues and 170,000 jobs. For countries such as Costa Rica, banana exports are vital. Bananas represent 8 percent of the country’s domestic product, bring in $500 million in hard-currency earnings, and employ one-fifth of the labor force. The presidents of Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, and Venezuela held a summit February 11, 1993, in Ecuador and issued a declaration rejecting the EU banana-marketing guidelines as a violation of GATT and principles of trade liberalization. However, following the formal adoption of the banana decision by the EU in July 1993, the EU and four Latin American nations (Costa Rica, Colombia, Nicaragua, and Venezuela) cut a deal in March 1994. The four countries agreed to drop their GATT protest in exchange for modifications in the restrictions they face. Guatemala refused to sign the agreement, and Ecuador, Panama, and Mexico lodged protests. The economics of production are clearly in favor of the Latin producers. The unit-cost of production in the Caribbean is nearly 2.5 times what it is for Latin American producers. For some producers, such as Martinique and Guadeloupe, the cost difference is even higher. The EU quota therefore results in major trade diversion. The affected Latin nations have used various means at the international level to get the EU to modify its position. In addition to the summit, many are engaged in lobbying in Brussels as well as the individual EU-member capitals. They have also sought the support of the United States, given its interests both in terms of U.S. multinational corporations’ involvement in the banana trade as well as its investment in encouraging economic growth in the developing democracies of Latin America.

The U.S. Position Initial U.S. reaction was that of an interested observer. The United States provided support and encouragement for the Latin Americans in their lobbying efforts in Geneva, Brussels, and the European capitals. However, in October 1994, the U.S. announced plans to start a year-long investigation of the EU’s banana restrictions, with sanctions against European imports as a possibility. This action broke new ground in trade disputes. While governments traditionally have started trade wars as a means of protecting domestic jobs and key industries, the banana dispute involves U.S. investment and overseas markets more than it does jobs at home. The probe was requested by Chiquita and the Hawaii Banana Industry Association, whose 130 small family farms constitute the entire banana-growing contingent. Although only 7,000 of the company’s 45,000 employees are in the United States, Chiquita officials argued that the value added by the company’s U.S. workers—marketers, shippers, and distributors—make it a major agricultural priority. The U.S. challenge was ‘‘not politically prudent,’’ because the United States does not even export bananas. However, 12 senators sent a letter to Mr. Mickey Kantor (U.S. trade representative, 1993 to 1996) warning against the dangerous precedent if the EU banana regime went unchallenged. Unless deterred, the EU could possibly employ similar measures for other agricultural products, especially those that the United States does export. The United States is, however, in favor of a WTO waiver to the EU to provide support to its former colonies. The contention is that the EU feels that it can, within this waiver, take any measures it deems necessary regardless of the impact on other WTO members. The United States and the other four countries filing the complaint argued for a more narrow interpretation, which would mean a simple system of tariff protection supported by aid to increase the efficiency of some producers and help the remainder to retire or diversify. The tariff would, in effect, offset some of the cost differences in the EU markets. The United States argues that many ACP producers are not competitive because of their special circumstances (such as small average farm size of five acres/two hectares) as well as EU preferences, which have given the ACP nations a disincentive to become competitive or to diversify.

The Caribbean Position For many nations, banana exports are the mainstay of their economies (see Figure 3). Therefore, it was not

surprising that heads of government of the 13-member Caribbean Community (CARICOM) approved a resolution February 24, 1993, supporting the EU guidelines. ‘‘No one country in this hemisphere is as dependent on bananas for its economic survival as the Windward Islands,’’ declared Ambassador Joseph Edsel Edmunds of St. Lucia. Referring to the criticism of the EU decision by the Latin nations, he added: ‘‘Are we being told that, in the interest of free trade, all past international agreements between the Caribbean and friendly nations are to be dissolved, leaving us at the mercy of Latin American states and megablocs?’’ He noted that Latin American banana producers command 95 percent of the world market and more than two-thirds of the EU market. Ambassador Kingsley A. Layne of St. Vincent and the Grenadines asserted that the issue at stake ‘‘is nothing short of a consideration of the right of small states to exist with a decent and acceptable standard of living, self-determination, and independence. The same flexibility and understanding being sought by other powerful partners in the WTO in respect of their specific national interests must also be extended to the small island developing states.’’ The highest levels of dependence on banana exports can be found in the Windward Islands countries: St. Lucia (19.7 percent), St. Vincent and Grenadines (22.3 percent), and Dominica (18.1 percent). After the WTO decision was rendered, the Caribbean nations have tried to strengthen alliances with European parliamentarians and have mobilized international opinion to continue to challenge the WTO ruling. ‘‘The decision represents a failure by the WTO, in its blind pursuit of free trade, to take into account the interests of small developing countries,’’ said Marshall Hall, chairman of the Caribbean Banana Exporters

Association. The Windward Islands, especially, are worried that the WTO ruling will further discourage farmers in the region who are already reducing quantities of fruit for export. St. Lucia’s banana exports have declined from 132,000 tons in 1992 to just 42,000 tons in 2009. The number of banana farmers has also fallen from 10,000 to 1,800 today, as the industry is forced to produce the quality fruit the market demands while facing stronger competition and lower prices. The country’s exports of bananas (known locally as ‘‘green gold’’) have dropped more than 60 percent in the past decade. The minister of tourism estimates that every acre of land used for tourism is three times as profitable as one used for growing bananas. Those farmers who have stayed in the business, he describes as ‘‘hard core and genuine.’’ It is they, he said, who are now producing the quality of bananas that the market is demanding. The future of the industry now seems to lie in exporting under the ‘‘fair trade’’ label. Caribbean bananas are grown mainly on small family farms, with intensive and justly paid labor and low usage of agro-chemical inputs. That inevitably results in lower yields and higher average cost. But many consumers are willing to pay a fair, if slightly higher, price for such an ethical and quality product—as they do for free-range and fair trade products.

The Corporate Position The two largest producer and marketers of bananas are both U.S.-based companies: Dole Food Company and Chiquita Brands International. Each accounts for just over a quarter of all bananas traded internationally. Then comes Fresh Del Monte Produce, controlled by the Chilean-based IAT Group (capital held in the United Arab Emirates), which controls approximately 16 percent of the banana trade. Fresh Del Monte Produce headquarters is Miami, Florida. The fourth biggest banana export company is ![]() Bananera Noboa (Bonita brand), part of the largest Ecuadorian conglomerate, Grupo Noboa, which controls a quarter of Ecuador’s exports and, therefore, about 13 percent of total world trade. In fifth place is the Irish fruit company Fyffes, with an estimated 7 percent share (see Figure 4).

Bananera Noboa (Bonita brand), part of the largest Ecuadorian conglomerate, Grupo Noboa, which controls a quarter of Ecuador’s exports and, therefore, about 13 percent of total world trade. In fifth place is the Irish fruit company Fyffes, with an estimated 7 percent share (see Figure 4).

The dispute has also pitted U.S. multinationals (Chiquita, Dole, and Del Monte) against the Europeans (Fyffes). Since 1996, the European group controls virtually all of the banana shipping and marketing from such markets as Belize, Suriname, Jamaica, and the Windward Islands. Chiquita, in particular, complains that the EU is arranging insider deals for Fyffes to exempt them from export licensing fees imposed by Latin American nations that have agreed with the EU, or even to secure them a slice of the export business from Latin American markets where they have no foothold at present. The EU’s licensing system has transferred 50 percent or more of U.S. or Latin American companies’ import rights principally to EU firms. The Caribbean nations and the EU assert that the United States is taking its action solely to support the world’s largest banana trader, Chiquita, because it wields great political influence.

Questions for Discussion

1. If you were a member of the Organization of American States (of which all of the Caribbean and Latin American countries mentioned in the case are members) and its Permanent Council (which must react to two opposing statements concerning the EU decision), with which one would you side?

2. Given the WTO’s decision, what are the alternatives for the EU and the Caribbean banana growers?

3. What types of strategic moves will an international marketing manager of a Latin American banana exporter make?