NOVA INTERNATIONAL (MACEDONIA)

The summer of 2003 in Skopje, Macedonia, had been one of the hottest on record. Ivan Novakovski, however, was not out enjoying the cool of the evening and the lively nightlife of the sidewalk cafes of Skopje, but sat in his office at the Nova International School. As both the Assistant Director of Nova and a son of the founding family, Ivan was concerned that the school was making a mistake by continuing to price and invoice all customers in U.S. dollars. As the glow of the Millennium Cross—the largest free-standing cross in the world— shone from the top of Vodno Mountain overlooking Skopje, he returned to his analysis. MACEDONIA AND NOVA INTERNATIONAL Macedonia is a landlocked country on the Balkan Peninsula in southeastern Europe. Formerly the southernmost part of the Socialist Federated Republic of Yugoslavia, the country’s 2 million inhabitants gained their independence from Yugoslavia on September 8, 1991. The country had long been the poorest of the Yugoslavian provinces, and the years following independence were difficult as the economy stumbled into market economics while suffering the ravages of a region wracked by war. Macedonian businesses were no longer protected competitors in the Yugoslavian marketplace, and many found themselves unprepared for the shock of open markets and competition. The war in nearby Bosnia, the imposition of international sanctions on Serbia, and the neighboring Kosovo crisis in 1999 all delivered successive shocks to Macedonia’s struggling trade-based economy at the end of the millennium. In 2001 economic conditions worsened again, this time as a result of an ethnic Albanian uprising with the country. Gross domestic product shrank 4.5 percent, borders were periodically closed, and government spending spiraled into deficit as security expenditures rose. Finally, with an unusual degree of quiet, 2002 and 2003 had brought two full years of relative calm and slow economic recovery. Venera Novakovski opened the Nova Language Institute in Skopje in late 1991, immediately following Macedonian independence. Like many markets throughout eastern and southern Europe, the movement towards free market economics had created a number of international business opportunities, one of which was language training. The language institute’s growing reputation led to the expansion of the school in 1996 from language training only to become the first private school in Macedonia, providing both primary and secondary educational services. Because Nova was the first private educational institution in Macedonia, it found itself classified as a for-profit company, complete with tax liabilities. Macedonia had not developed a notfor-profit institutional and legal structure which most educational institutions worldwide depend upon. In the early years Nova was categorized as the ‘‘American School,’’ where foreign expatriates sent their children to school while stationed in Macedonia. These expatriates were often in Macedonia for extended stays (two to five years, typically), and finding educational services which were both English-language and accredited outside of Macedonia was very valuable. The expatriate

community was growing rapidly as more and more multinational companies were investing in Macedonia, and as a result more foreign governments were increasing their presence and delegations in the former Yugoslavian state. The Novakovski family was particularly proud of the multitude of accreditation hurdles which they had been able to overcome in a short period of time. Nova was now accredited by the Northwest Association of Accredited Schools in the United States and the U.S. Department of State, and had been a facilitator for the SAT and ACT tests used in North America for student educational advancement for a number of years. Student enrollment growth was strong and steady. By 2003 there were 193 students enrolled in Nova. Roughly 25 percent of the high school students (grades 9–12) and 50 percent of the primary school students (grades 1–8) were international. It was expected that if the school were to actually expand some specific programs and recreational

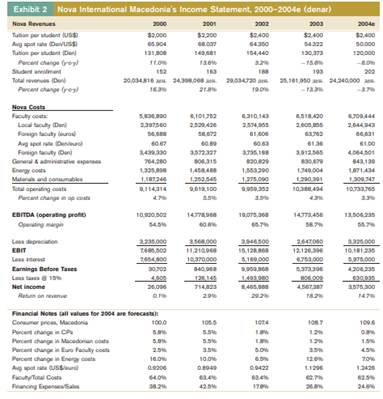

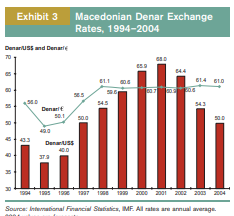

facilities, it could easily be looking at more than 400 students in three to four years. The school’s core educational facilities were capable of supporting 450 students on a full time basis. As illustrated by Exhibit 2, Nova’s income statement for the 2000–2004 period, the school had seen its financial results finally brighten in recent years. Although marginally profitable in 2000 and 2001, the school had finally shown substantial profits in 2002 and 2003. Profitability had seemingly peaked in 2002 with a 29 percent return on revenue. The Novakovski family’s many years of sacrifice and commitment was finally starting to pay off. But 2003 had proven a bit of disappointment, as revenues fell and costs rose. The school had closed 2003 with 4.5 million Macedonian denar (Den or MKD) in profit, down considerably from the year before. Ivan believed the problem to be in the school’s revenue structure, not its cost structure. Costs had been tightly controlled for many years, and 2003 was no different. But the school’s revenues had fallen two years running, and it was largely a result of the rising value of the Macedonian denar. This alone caused a bit of chuckle on Ivan’s part; the denar had long been the subject of ridicule, but was now rising against the downtrodden U.S. dollar. The Macedonian denar had been introduced in April of 1992 immediately following independence. (Its name was derived from the ancient Roman monetary unit, the denarius.) If Ivan’s estimates for the coming year were correct, 2004 would show little improvement. NOVA’S CURRENCY Because of its origins as a language institute and its early relationship with both the U.S. State Department and a number of major American companies, tuition was priced and paid in U.S. dollars. This was true for all students, domestic or international, and had never really met with any significant opposition. As an English language school, the payment of tuition in dollars was in many ways considered just another indicator of the school’s more global culture. The Macedonian ![]() (Den) was now pegged within a small band to the euro. Macedonia was offi- cially classified as a European Union Candidate Country, which meant that it had no guaranteed membership date, but that it was expected to move toward membership in the foreseeable future. As a result, the Macedonian government managed the value of the

(Den) was now pegged within a small band to the euro. Macedonia was offi- cially classified as a European Union Candidate Country, which meant that it had no guaranteed membership date, but that it was expected to move toward membership in the foreseeable future. As a result, the Macedonian government managed the value of the ![]() versus the euro—it had hovered around Den60/D for years, but largely ignored value changes against the U.S. dollar. The

versus the euro—it had hovered around Den60/D for years, but largely ignored value changes against the U.S. dollar. The ![]() had weakened steadily against the dollar from 1995 to mid-2002. But since then the direction had changed, with the denar closing in on Den50/$. Although not shown, the dollar itself had fallen considerably against the euro in recent years. The dollar had fallen to $1.17/D in June of 2003. Although it had recovered a bit in the last two months, trading at $1.13/D, the magnitude of its fall had been very unsettling. Dollar tuition was now resulting in fewer and fewer euros and Macedonian

had weakened steadily against the dollar from 1995 to mid-2002. But since then the direction had changed, with the denar closing in on Den50/$. Although not shown, the dollar itself had fallen considerably against the euro in recent years. The dollar had fallen to $1.17/D in June of 2003. Although it had recovered a bit in the last two months, trading at $1.13/D, the magnitude of its fall had been very unsettling. Dollar tuition was now resulting in fewer and fewer euros and Macedonian ![]() . Ivan’s worry was that Nova’s currency of cash flows was not really being well-served by tuition priced, stated, and paid in U.S. dollars. It was the currency of tradition at Nova, and it was the preferred currency of the American expatriate customer base. Although this expatriate segment was not more than 20 percent of all students, it had been the primary growth segment in the past few years. Nova’s cash inflows were simple: receipts from tuition made up 99 percent of the school’s net revenues (individual and corporate contributions occasionally yielded some income). The expense side, however, was a bit more diverse. Roughly half of operating expenses were faculty cost, both salary and benefits. Of that, most were paid in euros. This was a result of many faculty members being visitors from many other European countries. In addition to the operating expenses, financing costs—interest—were paid in euros as a result of recent debt extended by the World Bank to Nova for facilities renewal and expansion.1 With 75 percent of all revenues coming from Macedonian residents, domestic residents, Ivan wondered whether the tuition should not be paid in

. Ivan’s worry was that Nova’s currency of cash flows was not really being well-served by tuition priced, stated, and paid in U.S. dollars. It was the currency of tradition at Nova, and it was the preferred currency of the American expatriate customer base. Although this expatriate segment was not more than 20 percent of all students, it had been the primary growth segment in the past few years. Nova’s cash inflows were simple: receipts from tuition made up 99 percent of the school’s net revenues (individual and corporate contributions occasionally yielded some income). The expense side, however, was a bit more diverse. Roughly half of operating expenses were faculty cost, both salary and benefits. Of that, most were paid in euros. This was a result of many faculty members being visitors from many other European countries. In addition to the operating expenses, financing costs—interest—were paid in euros as a result of recent debt extended by the World Bank to Nova for facilities renewal and expansion.1 With 75 percent of all revenues coming from Macedonian residents, domestic residents, Ivan wondered whether the tuition should not be paid in ![]() or euros rather than dollars. But where was the school’s future growth really based? Many of the Macedonian students were now moving on to educational and job opportunities

or euros rather than dollars. But where was the school’s future growth really based? Many of the Macedonian students were now moving on to educational and job opportunities

in western Europe. And the Macedonian government had continued to pursue EU membership aggressively, arguing that the true economic future of the country rested with the EU. EU membership meant the euro as the currency of choice.

Case Questions

1. Why has Nova International used the U.S. dollar as the currency of invoice since its inception? Would it make sense to change this to either the Macedonian ![]() or the euro?

or the euro?

2. Take a hard look at the income statement presented. What is your assessment of the school’s business prospects? Why have revenues seemingly fallen in recent years? What costs have the greatest impact on the school’s financial results over the period shown?

3. What would you recommend that Ivan ![]() do about tuition? If you believe Nova should change to the euro or

do about tuition? If you believe Nova should change to the euro or ![]() , at what rate would you set the new tuition payment?

, at what rate would you set the new tuition payment?