CASE

IKEA: FURNISHING THE WORLD

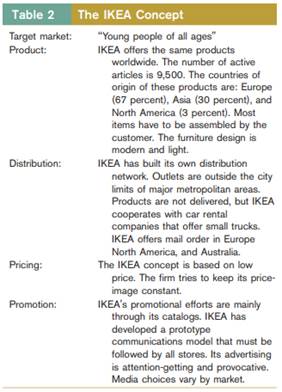

IKEA, the world’s largest home furnishings retail chain, was founded in Sweden in 1943 as a mail-order company and opened its first showroom ten years later. From its headquarters in Almhult, Sweden, IKEA has since expanded to worldwide sales of $30 billion from 301 outlets in 38 countries (see Table 1). In fact, the second store that IKEA built was in Oslo, Norway. The IKEA Group owns 267 stores in 25 countries: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, China, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The other 34 stores are owned and run by franchisees outside the IKEA Group in 16 countries/territories: Australia, the United Arab Emirates, Cyprus, Greece, Hong Kong, Iceland, Israel, Kuwait, Malaysia, the Netherlands, Romania, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Spain, Taiwan, and Turkey. IKEA first appeared on the Internet in 1997 with the World Wide Living Room Web site. IKEA attracted 561 million visits (2009). The IKEA Group’s new organization has three regions: Europe, North America, and Asia-Pacific. The international expansion of IKEA has progressed in three phases, all of them continuing at the present time: Scandinavian expansion, begun in 1963; West European expansion, begun in 1973; and North American expansion, begun in 1976. Of the individual markets, Germany is the largest, accounting for 16 percent, followed by the U.S. at 15 percent of company sales. The phases of expansion are detectable in the worldwide sales shares depicted in Figure 1. ‘‘We want to bring the IKEA concept to as many people as possible,’’ IKEA officials have said. The company estimates that over 590 million people visit its showrooms annually. THE IKEA CONCEPT Ingvar Kamprad, the founder, formulated as IKEA’s mission to ‘‘offer a wide variety of home furnishings of good design and function at prices so low that the majority of people can afford to buy them.’’ The principal target market of IKEA, which is similar across countries and regions in which IKEA has a presence, is composed of people who are young, highly educated, liberal in their cultural values, white-collar workers, and not especially concerned with status symbols. IKEA follows a standardized product strategy with a universally accepted assortment around the world. Today, IKEA carries an assortment of thousands of different home furnishings that range from plants to pots, sofas to soup spoons, and wine glasses to wallpaper. The smaller items are carried to complement the bigger ones. IKEA has very limited manufacturing of its own, but designs all of its furniture. The network of subcontracted manufacturers numbers 1,220 in 55 different countries. The top five purchasing countries are China (20 percent), Poland (18 percent), Italy (8 percent), Germany (6 percent), and Sweden (5 percent). IKEA had 31 trading service offices in 26 countries with 28 distribution centers and 11 customer distribution centers in 16 countries. IKEA’s strategy is based on cost leadership secured by contract manufacturers, many of which are in low-laborcost countries and close to raw materials, yet accessible to logistics links. Extreme care is taken to match manufacturers with products. Ski makers—experts in bent wood— have been contracted to make armchairs, and producers of supermarket carts have been contracted for durable sofas. High-volume production of standardized items allows for significant economies of scale. In exchange for long-term contracts, leased equipment, and technical support from IKEA, the suppliers manufacture exclusively at low prices for IKEA. IKEA’s designers work with the suppliers to build savings-generating features into the production and products from the outset. If sales continue at the forecasted rate, by 2010 IKEA will need to source twice as much material as today. Because Russia is a major source of lumber, IKEA aims to turn it into a major supplier of finished products in the future. IKEA has some of its production as well, constituting 12 percent of its total sales. IKEA has operations and offices in Sweden, Russia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Germany, Slovakia, Hungary, Ukraine, Portugal, China, and the United States. The Swedwood Group is a fully integrated international industrial group of IKEA, which consists of more than 50 production units and offices in 12 countries across three continents. IKEA consumers have to become ‘‘prosumers’’—half producers, half consumers—because most products have to be assembled. The final distribution is the customer’s

responsibility as well. Although IKEA expects its customers to be active participants in the buy-sell process, it is not rigid about it. There is a ‘‘moving boundary’’ between what consumers do for themselves and what IKEA employees will do for them. Consumers save the most by driving to the warehouses themselves, putting the boxes on the trolley, loading them into their cars, driving home, and assembling the furniture. Yet IKEA can arrange to provide these services at an extra charge. For example, IKEA cooperates with car rental companies to offer vans and small trucks at reasonable rates for customers needing delivery service. Additional economies are reaped from the size of the IKEA outlets; the blue-and-yellow buildings average 300,000 square feet (28,000 square meters) in size. IKEA stores include babysitting areas and cafeterias and are therefore intended to provide the value-seeking, car-borne consumer with a complete shopping destination. IKEA managers state that their competitors are not other furniture outlets but all attractions vying for the consumers’

free time. By not selling through dealers, the company hears directly from its customers. Management believes that its designer-to-user relationship affords an unusual degree of adaptive fit. IKEA has ‘‘forced both customers and suppliers to think about value in a new way in which customers are also suppliers (of time, labor, information, and transportation), suppliers are also customers (of IKEA’s business and technical services), and IKEA itself is not so much a retailer as the central star in a constellation of services.’’ Figure 2 provides a presentation of IKEA’s value chain. Although IKEA has concentrated on companyowned, larger-scale outlets, franchising has been used in areas in which the market is relatively small or where uncertainty may exist as to the response to the IKEA concept. These markets include Hong Kong and the United Arab Emirates. IKEA uses mail order in Europe, North America, and Australia. IKEA offers prices that are 30 to 50 percent lower than fully assembled competing products. This is a result of large-quantity purchasing, low-cost logistics, store locations in suburban areas, and the do-it-yourself approach to marketing. IKEA’s prices do vary from market to market, largely because of fluctuations in exchange rates and

differences in taxation regimes, but price positioning is kept as standardized as possible. IKEA’s operating margins of approximately 10 percent are among the best in home furnishings (as compared to 5 percent at U.S. competitor Pier 1 Imports and 7.7 percent at Target). This profit level has been maintained while the company has cut prices steadily. For example, the Klippan sofa’s price has decreased by 40 percent since 1999. IKEA’s promotion is centered on the catalog. A total of 198 million copies of the catalog have been printed in 56 editions and 27 languages. The catalogs are uniform in layout except for minor regional differences. The company’s advertising goal is to generate word-of-mouth publicity through innovative approaches. The IKEA concept is summarized in Table 2. IKEA Food Services reported sales of $1.5 billion. The IKEA restaurant and Swedish food market are the two elements that together make up IKEA food services. Both encourage people to visit the IKEA store and spend more time there; in this way, they support the store’s total home furnishing sales.

IKEA IN THE COMPETITIVE ENVIRONMENT IKEA’s strategy positioning is unique. As Figure 3 illustrates, few furniture retailers anywhere have engaged in

long-term planning or achieved scale economies in production. European furniture retailers, especially those in Sweden, Switzerland, Germany, and Austria, are much smaller than IKEA. Even when companies have joined forces as buying groups, their heterogeneous operations have made it difficult for them to achieve the same degree of coordination and concentration as IKEA. Because customers are usually content to wait for the delivery of furniture, retailers have not been forced to take purchasing risks. The value-added dimension differentiates IKEA from its competition. IKEA offers limited customer assistance but creates opportunities for consumers to choose (for example, through informational signage), transport and assemble units of furniture. The best summary of the competitive situation was provided by a manager at another firm: ‘‘We can’t do what IKEA does, and IKEA doesn’t want to do what we do.’’ IKEA IN THE UNITED STATES After careful study and assessment of its Canadian experience, IKEA decided to enter the U.S. market in 1985 by establishing outlets on the East Coast and, in 1990, in Burbank, California. In 2009, a total of 37 stores (12 in the Northeast, 8 in California, and others in Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, Oregon, Texas, Utah, and Washington State) generated sales of more than $4 billion. The overwhelming level of success in 1987 led the company to invest in a warehousing facility near Philadelphia that receives goods from Sweden as well as directly from suppliers around the world. Plans call for five to six additional stores annually over the next 25 years, concentrating on the northeastern United States and California. IKEA’s first U.S. manufacturing operation opened in 2008 in Virginia. Success today has not come without compromises. If you are going to be the world’s best furnishings company, you have to show you can succeed in America, because there is so much to learn here. Whereas IKEA’s universal approach had worked well in Europe, the U.S. market proved to be different. In some cases, European products conflicted with American tastes and preferences. For example, IKEA did not sell matching bedroom suites that consumers wanted. Kitchen cupboards were too narrow for the large dinner plates needed for pizza. Some Americans were buying IKEA’s flower vases for glasses. Adaptations were made. IKEA managers adjusted chest drawers to be an inch or two deeper because consumers wanted to store sweaters in them. Sales of chests increased immediately by 40 percent. In all, IKEA has redesigned approximately one-fifth of its product range in North America. Today, 45 percent of the furniture in the stores in North America is produced locally, up from 15 percent in the early 1990s. In addition to not having to pay expensive freight costs from Europe, this has also helped to cut stock-outs. And because Americans hate standing in lines, store layouts have been changed to accommodate new cash registers. IKEA offers a more generous return policy in North America than in Europe, as well as next-day delivery service. In hindsight, IKEA executives are saying they behaved like exporters, which meant not really being in the country. IKEA’s adaptation has not meant destroying its original formula. Its approach is still to market the streamlined and contemporary Scandinavian style to North America by carrying a universally accepted product—range but with attention to product lines and features that appeal to local preference. The North American experience has caused the company to start remixing its formula elsewhere as well. Indeed, now that Europeans are adopting some American furnishing concepts (such as sleeper sofas), IKEA is transferring some American concepts to other markets such as Europe.

Questions for Discussion

1. What has allowed IKEA to be successful with a relatively standardized product and product line in a business with strong cultural influence? Did adaptations to this strategy in the North American market constitute a defeat of its approach?

2. Which features of the ‘‘young people of all ages’’ are universal and can be exploited by a global/regional strategy?

3. Is IKEA destined to succeed everywhere it cares to establish itself?