PERFORMANCE APPRAISAL AT FEDERATION HOSPITAL Michelle Brown

Organisation background1 Federation Hospital provides healthcare services, including the full range of in-patient, day-case and out-patient services. It employs 2,200 ‘whole time equivalent’ (WTE) staff. The hospital is struggling to meet the growing demand for medical services. With the aging of the population and the hefty costs of attending a local doctor, many patients are presenting with serious conditions which are more costly and time consuming to treat. The government, in response to pressures from the general public, has instituted performance standards for hospitals; for example, defining the amount of time it should take for patients to be treated based on their medical condition.

The history of performance appraisal at Federation Hospital Performance appraisals at Federation Hospital were first implemented for senior managers and professional employees in 1998, principally as a development tool. This system operated until 2005 when a new CEO was appointed. The new (American) CEO believed that performance appraisals play a key communication role in an organisation. Both supervisors and employees become aware of the objectives of the organisation and work out how their job will assist with the achievement of the organisations objectives. Further, the CEO was keen to establish a ‘performance culture’ in the organisation. According to the CEO: Performance culture is at the heart of competitive advantage in the twenty-first century. With a performance culture we can derive the most from the limited funds available for health care. Further, the CEO as of the view that in order to be effective, appraisals had to influence pay increases and had to apply to everyone in the organisation.

Not all members of the senior management team were supportive of change to the appraisal system. Some senior managers argued that it would create an individualistic culture that wouldbe incompatible with the team-based work of the nonmanagerial staff in the hospital. Others managers wanted to see a developmentally focused system appraisal system. Medical technologies and health care practices are constantly evolving and the hospital needed to have a mechanism to help keep staff up to date. The HR department at the hospital spent the next 18 months reviewing performance appraisal systems in other organisations in order to fully understand the options and their applicability to the hospital. The new appraisal policy was circulated to all hospital staff (managerial and non-managerial) in June 2007. Over the next few months, supervisors were trained how to complete the new online forms and given some tips on how to provide negative feedback to their employees. The revised appraisal policy at Federation Hospital placed importance on setting measurable individual objectives. The policy document outlines the principles underpinning individual objective setting as following the acronym ‘SMART’: objectives should be specific, measurable, agreed/achievable, realistic and timebound, with the form of measurement for each objective to be agreed at the time that they are set.

The appraisal process Mechanics Under the new system, Federation Hospital performance objectives cascade downward through the organisation. The business plan is formulated by December/January each year and reviews conducted during February and March for senior managers in which their performance objectives for the coming year are established. The majority of appraisals for non-managerial employees take place during April and May. Non managerial employees often complain that: My manager just passes down their objectives onto me. I am a lab technician so there is not much that I can do to affect the performance of the hospital. Another frequent complaint is the high level of managerial staff turnover in the hospital because of resignations, promotions, transfers and secondments.

This level of managerial change makes it difficult for the manager to develop a good understanding of the work of the employee and effectively assess their performance. High managerial turnover also inhibits the development of a close working relationship between manager and employee. Better quality reviews occur when both parties know each other well leading to a more open and useful discussion at the performance review.

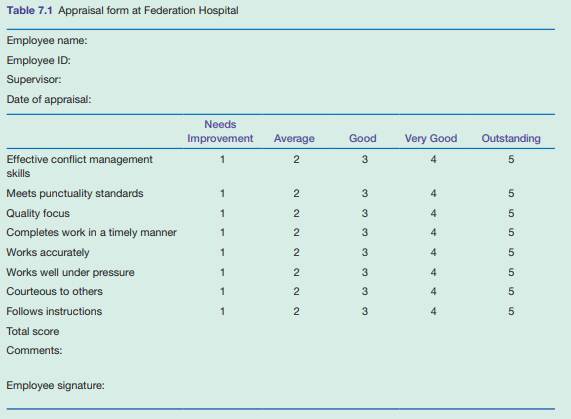

Coverage Experience with the pre-2007 appraisal system demonstrated that senior managers varied in their willingness to undertake appraisals of their junior managers. Senior managers would complain that: … appraisals are time consuming and get in the way of good relationships with my employees. As a result only up to a third of those whose performance was supposed to be assessed was actually assessed. The post-2007 appraisal system built in incentives for managers to undertake their appraisal responsibilities: one of the performance objectives of managers is to appraise their staff. The timely completion rates of appraisals is now near 100 per cent, though as one HR official noted, the average rating score for employees at Federation Hospital has also increased from 3.1 to 3.9. Documentation The appraisal system rates employees on a 5-point scale (1 = needs improvement; 5 = outstanding). A copy of the form supplied by HR to all supervising managers is provided in Table 7.1. Reactions among managers to the form were mixed. Some managers felt that the form was a good general framework to help them assess their employee’s performance. Other managers were very unclear about how they were to evaluate their employees. As one manager noted, ‘what is an outstanding in conflict management?’ The appraisal meeting Once a year the supervisor and the employee have a face-to-face meeting to review progress towards the performance goals set at the beginning of the evaluation cycle and come up with a performance rating. The younger employees regarded the appraisal meeting as a good opportunity to find out how they were doing. For the most part, younger employees were seen to be

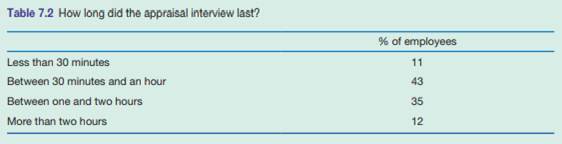

more receptive to feedback so the managers tended to spend more time with them. The more experienced employees resented the appraisal meetings. I have been doing my job for the last 15 years. I do not need to have someone who has never done the job tell me what to do. Managers were required to find ‘areas for improvement’ for each of their employees, which employees interpreted as finding fault with their work. I meet all of my performance objectives but my supervisor is obsessed with having a tidy desk. He dropped my performance rating from a 4 to a 3. It is insane. My job is to look after patients and that in my mind trumps a tidy desk. Table 7.2 provides a summary of the amount of time spent in the appraisal meeting and shows that the majority of employees reported interviews of at least 30 minutes, with 47 per cent having interviews of more than an hour. Some managers like to keep the meetings short as some employees regard the meeting as an opportunity to review the manager’s performance: Last week I had to cut a meeting short as the receptionist just went on and on about how hard it is to work here with such old technology. She said it was my fault she was not performing at an acceptable level.

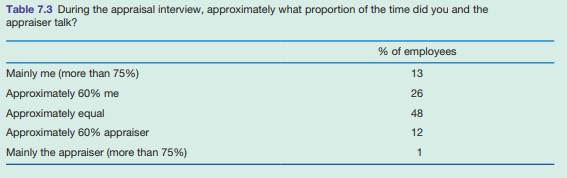

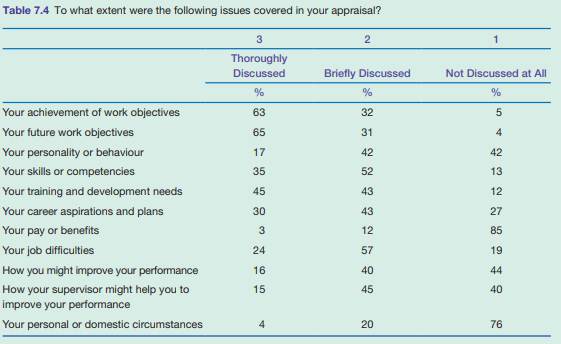

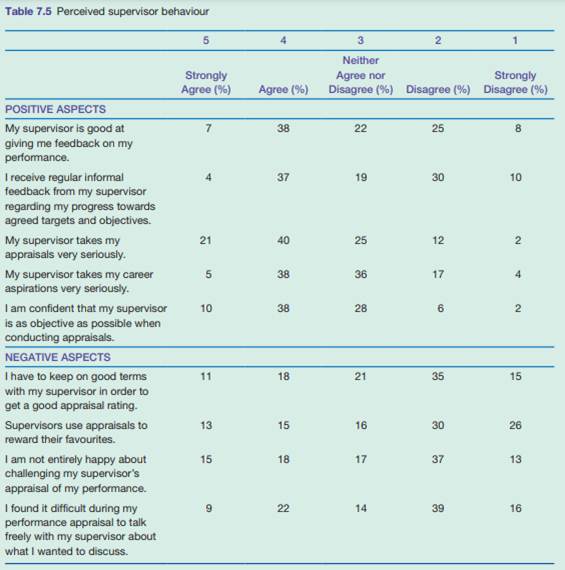

Table 7.3 provides a summary of the time the supervisor and the employee spent talking during theappraisal meeting. Judging from Table 7.3, appraisers were not usually dominating the interviews: only 1 per cent of employees reported that the manager talked for more than 75 per cent of time during the appraisal meeting. Almost half of the employees said that there was equal time spent by them and their supervisor talking during the appraisal meeting. Table 7.4 sets out the extent to which various issues were discussed during the appraisal meeting. The data in table demonstrates that managers focus on the extent to which work objectives have been met (63 per cent say thoroughly discussed) and the establishment of new objectives for the next evaluation cycle (65 per cent say thoroughly discussed). Less attention is given to the career development aspects: only 35 per cent say their skills or competences were thoroughly discussed. While many managers supported the idea of employee development, the problems lie in the implementation. The biggest problem was in finding the funds in the training budget to pay for costly external courses. Denying staff access to training was having a negative impact on perceptions of the appraisal system. In order for me to move up the management ladder of the hospital I need to do a Master’s degree. When I asked my supervisor during my appraisal meeting for support, she just smiled and said I wish I could assist but there is just no money. What is the point of the system if there is no money? In Table 7.5 employees provide data on what they think was positive and negative in their supervisor

appraisal behaviours. Supervisors were seen to be taking the process seriously with 61 per cent of appraises (strongly agreeing or agreeing) with the statement that ‘my supervisor takes my appraisals very seriously’. About half of the appraisees (48 per cent) were ‘confident that my supervisor is as objective as possible when conducting appraisals’. Some appraisees expressed concerns about the quality of the formal feedback they were receiving with 32 per cent of appraisees disagreeing or strongly disagreeing with the statement that ‘my supervisor is good at giving me feedback on my performance’. HR was particularly concerned with the data that suggested that a political element had entered into the appraisal process. About a third of appraisees agreed or strongly agreed that ‘I have to keep on good terms with my supervisor in order to get a good appraisal rating’ and that ‘supervisors use appraisals to reward their favourites’. Mid cycle reviews The formal annual reviews are supported by ‘mid cycle reviews’.

The policy document sees these as a ‘crucial element’ of the appraisal process. Regular informal feedback was intended to ensure that employees did not get into difficulties between formal appraisal meetings. Informal feedback could also reduce the level of emotion at the appraisal interview as the rating of the supervisor should come as ‘no surprise’ to the employee. The data in Table 7.5 suggests that informal feedback is not being regularly provided with 40 per cent of appraisees disagreeing or strongly disagreeing with the statement that ‘I receiveregular informal feedback from my supervisor regarding my progress towards agreed targets and objectives.’ Employees with a more positive experience point out that they have requested and received, additional mid cycle review. They saw mid cycle reviews as useful to fine-tune, and often to replace, objectives that had been rendered obsolete by a rapidly changing organisational environment. Mid cycle reviews allowed for individual objectives to be kept in line with changes in business strategy.

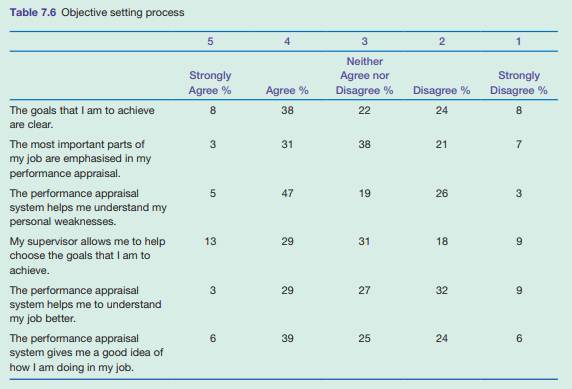

In addition to the lack of informal feedback there was some concern about the quality of the informal feedback. For some employees, the mid cycle reviews were rushed ‘corridor and canteen chats’ that tended to focus on the negatives (e.g. patient complaints) rather than any positives (e.g. successfully dealing with difficult patient families). Some employees worried that this would bias their performance rating: their manager would recall only the negatives at their formal appraisal meeting. Objective setting The increased emphasis on work objectives and measurability promoted by the CEO is reflected in the issues covered in the appraisal process, with employees reporting that the achievement and planning of work objectives were the most thoroughly discussed issues in the appraisal process (see Table 7.4). In Table 7.6 employees provide insights into the quality of the objective setting process. Supervisors were doing a good job at setting clear goals with 46 per cent agreeing or strongly agreeing with the statement ‘the

goals that I am to achieve are clear’. It appears that the goals were sometimes imposed on appraisees: only 42 per cent agreed or strongly agreed that ‘my supervisor allows me to help choose the goals that I am to achieve’. Some managers argue that employees are often not very good at setting objectives but rather than impose objectives would provide copies of their own objectives in advance of the review process. The imposition of objectives was a source of irritation for both supervisors and employees. Pushing employees could damage the relationship with an employee. However, the danger with imposing objectives on employees reluctant to accept them was that employees play ‘lip service’ to them and are not committed to their achievement. In some cases, imposing objectives was seen as necessary as employees often tried to game the system by setting easy objectives. As one employee notes: What I’ve learnt, as time goes by, is you’ve got to be careful, right at the outset, how you set your objectives because you can be over optimistic, unrealistic. There’s a danger of sitting down and thinking of all the things you’d love to do, or ideally should do, forgetting that you’ve got lots of constraints and you couldn’t in a month of Sundays achieve it. So I think quite a few of us have learnt there is a skill in setting objectives which are reasonable and stand a chance of being achieved. I think that that bit is probably more important than anything else. There is nothing more demoralising

than being measured against something which you yourself have declared as being in need of being done and finding that you couldn’t possibly do it. The connection between the objectives and an employee’s jobs was not clear for 32 per cent of employees. This seems to be due, in part, to the increasing emphasis on teamwork in the hospital but the emphasis on individual performance in the appraisal process. The focus on identifying and making improvements was clear to employees: 52 per cent agreed or strongly agreed with the statement: ‘the performance appraisal system helps me understand my personal weaknesses’.

Accuracy of appraisal HR encourages both supervisors and employees to collect data on performance throughout the year and then bring it along to the appraisal meeting. I always try to get my facts right first before approaching an employee, rather than going on hearsay. Try to establish some substance towards giving that feedback, and if they say it was just hearsay, you’ve got evidence to back it up. Supervisors prefer to rely on the objectives set at the beginning of the evaluation cycle. I basically look at her performance objectives and say well you agreed to this. These sorts of performance indicators are what we agreed on prior to this. This part here I don’t think you’re meeting. Employees bring along a variety of documentation to the appraisal meeting. I took lots of things along to the appraisal meeting. One of my objectives was to set up team objectives on the ward. I copied examples of these objectives and took them along. I showed reports I had done on the empowerment of patients, and gave her copies of patients’ meetings.

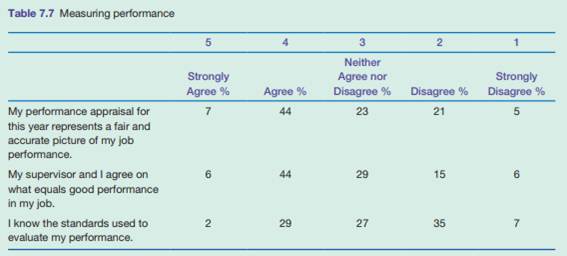

I used information to show that I had done things. I used these things to prove to her that I had achieved them. In Table 7.7 employees provide an assessment of the accuracy of their appraisal. A slim majority (51 per cent) agreed or strongly agreed that ‘my performance appraisal for this year represents a fair and accurate picture of my job performance’. For some employees the lack of accuracy may be related to ambiguity about the ‘standards used to evaluate my performance’ (42 per cent disagreed or strongly disagreed). There was also some uncertainty about what constitutes good performance with 50 per cent

agreeing or strongly agreeing with the statement: ‘My supervisor and I agree on what equals good performance in my job.’ Supervisors often get frustrated with their employees when they refuse to take responsibility for their performance. A nurse I was apprising said, ‘This is why I cannot do my job. This is why I cannot achieve this objective.’ And then trotted out a great list of problems with the job. One issue that is a source of frustration for employees is the absence of a publicly available summary of the performance ratings. While each employees rating is accessible to them via the staff intranet they have no idea of how their rating fits with the overall distribution of scores. How I can make sense of my rating when I do not know if this is high or low relative to other employees like me? And why can’t the hospital share this information? What are they sacred of? Performance payments The CEO of Federation Hospital introduced performance payments in 2007 as part of the new appraisal system. An employee’s rating was used to determine the percent increase in pay. As the budget situation of the hospital is always tight, they are unable to announce the amount of money associated with each performance rating.

Over the last few years the average individual performance payment has been 3 per cent. For some employees the amounts available are not worth the effort. I worked my tail off last year. Stayed back late and helped others when we were short staffed. And after tax all I got was a couple of hundred pounds for my efforts. Never again am I going to work so hard for so little. For some of the longer serving members of Federation Hospital there was no need for a financial incentive. They enjoyed the work in the hospital and the patients. I don’t need someone wielding a financial stick to tell me how to do my job or push myself.

Questions

1 How effective is the appraisal system at Federation Hospital? Think about its impact on employee performance and retention.

2 Should Federation Hospital retain the current appraisal system? Why or why not?

3 What challenges do managers at Federation Hospital face when rating employee performance?

4 How effective are the managers at evaluating employee performance?

5 How would you rate the fit between the appraisal system, the objectives of the hospital and nature of the work undertaken?

6 Should the CEO of Federation Hospital include a 360-degree feedback system for all managers? Why or why not?

7 Would a feedforward system be appropriate for Federation Hospital?