AKERMAN v. ORYX COMMUNICATIONS, INC.

This case arises out of a June 30, 1981, initial public offering of securities by ORYX, a company planning to enter the business of manufacturing and marketing abroad video cassettes and video discs of feature films for home entertainment. ORYX filed a registration statement and an accompanying prospectus dated June 30, 1981, with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for a firm commitment offering of 700,000 units. Each unit sold for $4.75 and consisted of one share of common stock and one warrant to purchase an additional share of stock for $5.75 at a later date.

The prospectus contained an erroneous pro forma unaudited financial statement relating to the eight month period ending March 31, 1981. It reported net sales of $931,301, net income of $211,815, and earnings of seven cents per share. ORYX, however, had incorrectly posted a substantial transaction by its subsidiary to March instead of April when ORYX actually received the subject sale’s revenues. The prospectus, therefore, overstated earnings for the eight month period. Net sales in that period actually totaled $766,301, net income $94,529, and earnings per share three cents. ORYX’S price had declined to four dollars per unit by October 12, 1981, the day before ORYX revealed the prospectus misstatement to the SEC. The unit price had further declined to $3.25 by November 9, 1981, the day before ORYX disclosed the misstatement to the public. After public disclosure, the price of ORYX rose and reached $3.50 by November 25, 1981, the day this suit commenced.

Plaintiffs allege that the prospectus error rendered ORYX liable for the stock price decline pursuant to sections 11 and 12(2) of the Securities Act of 1933. In July 1982, ORYX moved for summary judgment on the grounds, inter alia, that the misstatement was not material for purposes of establishing liability under section 11 and that the misstatement had not actually caused the price decline for purposes of damages under section 11. ORYX also moved for summary judgment on the section 12(2) claims, again arguing that the error was immaterial and also that plaintiffs lacked “privity,” as required under section 12(2), to maintain a suit against ORYX as an issuer because the offering was made pursuant to a “firm commitment underwriting.” In December 1982, plaintiffs brought the underwriters into the suit. The underwriters subsequently moved for summary judgment, making substantially the same arguments as had ORYX.

Section 11(a) of the 1933 Act imposes civil liability on the signatories of a registration statement if the registration statement contains a material untruth or omission of which a “person acquiring [the registered] security” had no knowledge at the time of the purchase1 … Plaintiffs in the Akermans’ situation, if successful, would be entitled to recover the difference between the original purchase price and value of the stock at the time of suit. . . . A defendant may, under section 11(e), reduce his liability by proving that the depreciation in value resulted from factors other than the material misstatement in the registration statement. . . . A defendant’s burden in attempting to reduce his liability has been characterized as the burden of “negative causation.”. . .

The district court determined that plaintiffs established a prima facie case under section 11(a) by demonstrating that the prospectus error was material “as a theoretical matter.”. . . The court, however, granted defendants’ motion for summary judgment on damages under section 11(e), stating: “[Defendants] have carried their heavy burden of proving that the [ORYX stock price] decline was caused by factors other than the matters misstated in the registration statement.”. . . The precise issue on appeal, therefore, is whether defendants carried their burden of negative causation under section 11(e).

1. Section 11(a) provides in pertinent part: In case any part of the registration statement, when such part became effective, contained an untrue statement of a material fact or omitted to state a material fact required to be stated therein or necessary to make the statements therein not misleading, any person acquiring such security (unless it is proved that at the time of such acquisition he knew of such untruth or omission) may, either at law or in equity, in any court of competent jurisdiction, sue—

(1) every person who signed the registration statement:

(5) every underwriter with respect to such security. 15 U.S.C.s 77k(a).

Defendants’ heavy burden reflects Congress’ desire to allocate the risk of uncertainty to the defendants in these cases. . . . Defendants’ burden, however, is not insurmountable; section 11(e) expressly creates an affirmative defense of disproving causation. . . . The Akermans’ section 11(a) claim survived an initial summary judgment attack when the court concluded that the prospectus misstatement was material. . . . We note, however, that the district court held that the misstatement was material only “as a theoretical matter.”. . . As described below, this conclusion weighs heavily in our judgment that the district court correctly decided that the defendants had carried their burden of showing that the misstatement did not cause the stock price to decline.

The misstatement resulted from an innocent bookkeeping error whereby ORYX misposted a sale by its subsidiary to March instead of April. ORYX received the sale’s proceeds less than one month after the reported date. The prospectus, moreover, expressly stated that ORYX “expect[ed] that [the subsidiary’s] sales will decline.”. . . Indeed, Morris Akerman conceded that he understood this disclaimer to warn that ORYX expected the subsidiary’s business to decline. . . . Thus, although the misstatement may have been “theoretically material,” when it is considered in the context of the prospectus’pessimistic forecast of the performance of ORYX’s subsidiary, the misstatement was not likely to cause a stock price decline. . . . Indeed, the public not only did not react adversely to disclosure of the misstatement, ORYX’s price actually rose somewhat after public disclosure of the error.

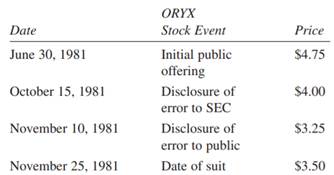

The applicable section 11(e) formula for calculating damages is “the difference between the amount paid for the security (not exceeding the price at which the security was offered to the public) and . . . the value thereof as of the time such suit was brought.”. . . The relevant events and stock prices are:

The price decline before disclosure may not be charged to defendants. . . . At first blush, damages would appear to be zero because there was no depreciation in ORYX’s value between the time of public disclosure and the time of suit. The Akermans contended at trial, however, that the relevant disclosure date was the date of disclosure to the SEC and not to the public. Under plaintiffs’ theory, damages would equal the price decline subsequent to October 15, 1981, which amounted to fifty cents per share. Plaintiffs attempted to support this theory by alleging that insiders privy to the SEC disclosure—ORYX’s officers, attorneys and accountants, and underwriters and SEC officials—sold ORYX shares and thereby deflated its price before public disclosure. . . . The district court attributed “at least possible theoretical validity” to this argument. . . . After extensive discovery, however, plaintiffs produced absolutely no evidence of insider trading. . . . Plaintiffs’ submissions and oral argument before us do not press this theory.

The Akermans first attempted to explain the public’s failure to react adversely to disclosure by opining that defendant-underwriter Moore & Schley used its position as market maker to prop up the market price. This theory apparently complemented the Akermans’ other theory that insiders acted on knowledge of the disclosure to the SEC to deflate the price before public disclosure. The Akermans failed after extensive discovery to produce any evidence of insider trading and have not pressed the theory on appeal.

The district court invited statistical studies from both sides to clarify the causation issue. Defendants produced a statistical analysis of the stocks of the one hundred companies that went public contemporaneously with ORYX. The study tracked the stocks’ performances for the period between June 30, 1981 (initial public offering date) and November 25, 1981 (date of suit). The study indicated that ORYX performed at the exact statistical median of these stocks and that several issues suffered equal or greater losses than did ORYX during this period. . . . Defendants produced an additional study which indicated that ORYX stock “behaved over the entire period . . . consistent[ly] with its own inherent variation.”. . .

Plaintiffs offered the following rebuttal evidence. During the period between SEC disclosure and public disclosure, ORYX stock decreased nineteen percent while the over-thecounter (OTC) composite index rose five percent (the first study). During this period, therefore, the OTC composite index outperformed ORYX by twenty-four percentage points. Plaintiffs also produced a study indicating that for the time period between SEC disclosure and one week after public disclosure, eighty-two of the one hundred new issues analyzed in the defendants’ study outperformed ORYX’s stock. Plaintiffs’ first study compared ORYX’s performance to the performance of the OTC index in order to rebut a comparison offered by defendants to prove that ORYX’s price decline resulted not from the misstatement but rather from an overall market decline. . . . The parties’ conflicting comparisons, however, lack credibility because they fail to reflect any of the countless variables that might affect the stock price performance of a single company. . . . The studies comparing ORYX’s performance to the other one hundred companies that went public in May and June of 1981 are similarly flawed. The studies do not evaluate the performance of ORYX stock in relation to the stock of companies possessing any characteristic in common with ORYX, e.g., product, technology, profitability, assets or countless other variables which influence stock prices, except the contemporaneous initial offering dates.

Granting the Akermans every reasonable, favorable inference, the battle of the studies is at best equivocal; the studies do not meaningfully point in one direction or the other. . . . Defendants met their burden, as set forth in section 11(e), by establishing that the misstatement was barely material and that the public failed to react adversely to its disclosure. With the case in this posture, the plaintiffs had to come forward with “specific facts showing that there is a genuine issue for trial.”. . . Despite extensive discovery, plaintiffs completely failed to produce any evidence, other than unreliable and sometimes inconsistent statistical studies and theories, suggesting that ORYX’s price decline actually resulted from the misstatement. . . . Summary judgment was properly granted.

SECTION 12(2) CLAIMS AGAINST ORYX

The Akermans also appeal the district court’s holding that they lack privity to maintain a suit against ORYX under section 12(2) of the Securities Act of 1933. Section 12(2) imposes liability on persons who offer or sell securities and only grants standing to “the person purchasing such security” from them. . . . This provision is a broad antifraud measure and imposes liability whether or not the purchaser actually relied on the misstatement.

The offering here was made pursuant to a “firm commitment underwriting,” as the prospectus indicated. Title to the securities passed from ORYX to the underwriters and then from the underwriters to the purchaser-plaintiffs. ORYX, therefore, was not in privity with the Akermans for section 12(2) purposes….

The Akermans nonetheless contend that ORYX may be held liable under section 12(2) as a participant in the offering. It is true that a person who makes a misrepresentation may be held liable as a “participant” even though he is not the immediate and direct seller of the securities. This is true, however, only if there is proof of scienter. . . . The Akermans completely failed to make a showing that ORYX possessed scienter. Therefore, summary judgment was proper.

We affirm the judgment on the plaintiffs’ section 11 and section 12(2) claims and . . . remand to the district court for further proceedings.