CASE STUDY:

A Family Planning Case Study: Pakistan and Bangladesh

John Bongaarts

Over the past half century many governments in developing countries have implemented family planning programs to provide access to and information about contraception methods. The initiation of these programs is usually followed by substantial increases in contraceptive use and declines in fertility. Unfortunately, it is difficult to determine the exact role of the family planning programs from these trends because it is likely that contraceptive use would have risen somewhat even in the absence of the program. This fact has made the estimation of net program impact difficult and controversial.

The gold standard for evaluating the impact of health interventions is to conduct experiments. Unfortunately, few large-scale controlled experiments have been conducted to assess family planning programs because they are expensive and take a long time to complete. The largest and most influential of these experiments—the Family Planning and Health Services Project (FPHSP)—began in the late 1970s in Matlab, Bangladesh. At that time, Bangladesh was one of the poorest and most highly agricultural countries in the world, and there was widespread skepticism that family planning would be accepted in such a traditional society

The FPHSP divided the rural Matlab district (population of 173,000 in 1977) into experimental and control areas of approximately equal size. The control area received the same (minimal) services as the rest of the country, whereas in the experimental area comprehensive high-quality family planning services were provided, aimed at reducing the costs (monetary, social, psychological, and health) of adopting contraception. The experimental area provided free services and supplies of a range of methods (pills, condoms, injectables, IUDs, and sterilization), home visits by well-educated female family planning workers, regular follow-up to address health concerns, comprehensive multimedia communication, and menstrual regulation* services. Outreach to husbands, leaders of household groups, and religious leaders addressed potential social and familial objections from men.

The impact of these intensive services on reproductive behavior was large and immediate. Within a year from the start of the program, the proportion of women using contraception in the experimental area rose from 5% to 28%. In contrast, little change occurred in the control area or in the rest of Bangladesh during the first few years. The rise in contraceptive prevalence in the experimental area led to a decline in fertility of about 25% below the level in the control area.a The Matlab experiment demonstrated that family planning programs can succeed even in traditional societies. The success of this program led the government of Bangladesh to adopt the Matlab model as its national family planning strategy

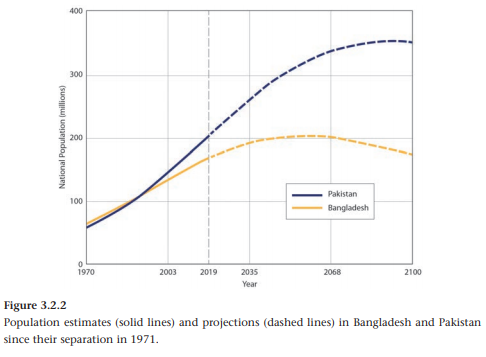

Figure 3.2.1 plots trends in fertility from 1970 to 2010 for Bangladesh and Pakistan. At the end of the 1970s the two countries had nearly the same high fertility of 6.8 births per woman, but trends diverged in subsequent decades. By the late 1990s fertility in Bangladesh had declined to 3.4 births per woman, while in Pakistan fertility still stood at 5.0. This difference in fertility was maintained, with Bangladesh reaching near replacement fertility of 2.2 births per woman in 2010–2015, a remarkably low level for such a poor country.

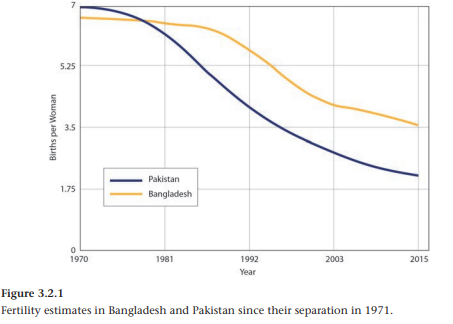

The contrasting fertility trends in these two countries can plausibly be attributed to differences in their family planning programs. Pakistan’s program has been weak, lacking government funds and commitment, although it has gradually improved over time. In contrast, Bangladesh has implemented one of the world’s most effective voluntary family planning programs, using the experience and lessons from the Matlab experiment. Fertility and population trends are also affected by the level of development and social and cultural factors, but these are unlikely to be an important explanation for the different country trajectories. Development levels, as measured by the Human Development Index, are nearly the same for Bangladesh and Pakistan.c Moreover, the two countries were united as one country from 1947 until Bangladesh was established after a civil war in 1971; they therefore share common cultural, religious, and government traditions. Pakistan’s neglect of family planning in the 1970s and 1980s led to much more rapid population growth than in Bangladesh (Figure 3.2.2). In 1980, the populations of the two countries were about the same size, but by 2050 Pakistan’s population is projected to be 50% larger than Bangladesh’s (307 compared with 202 million) and by 2100 Pakistan’s population is projected to be twice that of Bangladesh (352 compared with 174 million).b When populations are growing rapidly, delays in the implementation of family planning programs and in the fertility decline associated with them have major implications for future demographic trends and associated health and environmental impacts.