CASE

THE VENEZUELAN BOLIVAR BLACK MARKET

Rumor has it that during the year and a half that Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez spent in jail for his role in a 1992 coup attempt against the government, he was a voracious reader. Too bad his prison syllabus seems to have been so skimpy on economics and so heavy on Machiavelli.

‘‘Money Fun in the Venezuela of Hugo Chavez,’’ The Economist, February 13, 2004

It’s late afternoon on March 10, 2004, and Santiago opens the window of his office in Caracas, Venezuela. Immediately he is hit with the sounds rising from the plaza—cars honking, protesters banging their pots and pans, street vendors hawking their goods. Since the imposition of a new set of economic policies by President Hugo Chavez in 2002 such sights and sounds had become a fixture of city life in Caracas. Santiago sighed as he wished for the simplicity of life in the old Caracas. Santiago’s once-thriving pharmaceutical distribution business had hit hard times. Since capital controls were implemented in February of 2003, dollars had been hard to come by. He had been forced to pursue various methods—methods that were more expensive and not always legal—to obtain dollars, causing his margins to decrease by 50 percent. To add to the strain the Venezuelan currency, the bolivar (Bs), had been recently devalued (repeatedly). This had instantly squeezed his margins as his costs had risen directly with the exchange rate. He could not find anyone to sell him dollars. His customers needed supplies and they needed them quickly, but how was he going to come up with the $30,000—the hard currency—to pay for his most recent order?

POLITICAL CHAOS

Hugo Ch![]() tenure as president of Venezuela had been tumultuous at best since his election in 1998. After repeated recalls, resignations, coups, and re-appointments, the political turmoil had taken its toll on the Venezuelan economy as a whole, and its currency in particular. The short-lived success of the anti-Ch

tenure as president of Venezuela had been tumultuous at best since his election in 1998. After repeated recalls, resignations, coups, and re-appointments, the political turmoil had taken its toll on the Venezuelan economy as a whole, and its currency in particular. The short-lived success of the anti-Ch![]() coup in 2001, and his nearly immediate return to office, had set the stage for a retrenchment of his isolationist economic and financial policies.

coup in 2001, and his nearly immediate return to office, had set the stage for a retrenchment of his isolationist economic and financial policies.

On January 21, 2003, the bolivar closed at a record low—Bs1853/$. The next day President Hugo Chavez suspended the sale of dollars for two weeks. Nearly instantaneously, an unofficial or black market for the exchange of Venezuelan bolivars for foreign currencies (primarily U.S. dollars) sprouted. As investors of all kinds sought ways to exit the Venezuelan market, or simply obtain the hard-currency needed to continue to conduct their businesses (as was the case for Santiago), the escalating capital flight caused the black market value of the bolivar to plummet to Bs2500/$ in weeks. As markets collapsed and exchange values fell, the Venezuelan inflation rate soared to more than 30 percent per annum.

CAPITAL CONTROLS AND CADIVI

To combat the downward pressures on the bolivar, the Venezuelan government announced on February 5, 2003, the passage of the 2003 Exchange Regulations Decree. The decree took the following actions: 1. Set the official exchange rate at Bs1596/$ for purchase (bid) and Bs1600/$ for sale (offer); 2. Established the ![]() on de

on de ![]() on de Divisas (CADIVI) to control the distribution of foreign exchange; and 3. Implemented strict price controls to stem inflation triggered by the weaker bolivar and the exchange control-induced contraction of imports. CADIVI was both the official means and the cheapest means by which Venezuelan citizens could obtain foreign currency. In order to receive an authorization from CADIVI to obtain dollars, an applicant was required to complete a series of forms. The applicant was then required to prove that they had paid taxes the previous three years, provide proof of business and asset ownership and lease agreements for company property, and document the payment of current social security payments. Unofficially, however, there was an additional unstated requirement for permission to obtain foreign currency: that authorizations by CADIVI would be reserved for Ch

on de Divisas (CADIVI) to control the distribution of foreign exchange; and 3. Implemented strict price controls to stem inflation triggered by the weaker bolivar and the exchange control-induced contraction of imports. CADIVI was both the official means and the cheapest means by which Venezuelan citizens could obtain foreign currency. In order to receive an authorization from CADIVI to obtain dollars, an applicant was required to complete a series of forms. The applicant was then required to prove that they had paid taxes the previous three years, provide proof of business and asset ownership and lease agreements for company property, and document the payment of current social security payments. Unofficially, however, there was an additional unstated requirement for permission to obtain foreign currency: that authorizations by CADIVI would be reserved for Ch![]() supporters. In August 2003 an anti-Chavez petition had gained widespread circulation. One million

supporters. In August 2003 an anti-Chavez petition had gained widespread circulation. One million

signatures had been collected. Although the government ruled that the petition was invalid, it had used the list of signatures to create a database of names and social security numbers that CADIVI utilized to cross-check identities when deciding who would receive hard currency. President Chavez was quoted as saying ‘‘Not one more dollar for the ![]() ; the bolivars belong to the people.’’1

; the bolivars belong to the people.’’1

SANTIAGO’S ALTERNATIVES

Santiago had little luck obtaining dollars via CADIVI to pay for his imports. Because he had signed the petition calling for President Chavez’s removal, he had been listed in the CADIVI database as anti-Chavez, and now could not obtain permission to exchange bolivars for dollars. The transaction in question was an invoice for $30,000 in pharmaceutical products from his U.S.-based supplier. Santiago would then, in-turn, sell to a large Venezuelan customer who would distribute the products. This transaction, however, was not the first time that Santiago had had to search out alternative sources for meeting his U.S.-dollar obligations. Since the imposition of capital controls, the search for dollars had become a weekly activity for Santiago. In addition to the official process through CADIVI, he could also obtain dollars through the gray market, or the black market.

THE GRAY MARKET: CANTV SHARES

In May 2003, three months following the implementation of the exchange controls, a window of opportunity had opened up for Venezuelans—an opportunity that allowed investors in the Caracas stock exchange to avoid the tight foreign exchange curbs. This loophole circumvented the government-imposed restrictions, by allowing investors to purchase local shares of the leading telecommunications company CANTV on the Caracas’ bourse, and to then convert them into dollar-denominated American Depositary Receipts (ADRs) traded on the NYSE. The sponsor for CANTV ADRs on the NYSE was the Bank of New York, the leader in ADR sponsorship and management in the United States. The Bank of New York had suspended trading in CANTV ADRs in February after the passage of the decree, wishing to determine the legality of trading under the new Venezuelan currency controls. On May 26, after concluding that trading was indeed legal under the decree, trading resumed in CANTV shares. CANTV’s share price and trading volume both soared in the following week.2 The share price of CANTV quickly became the primary method of calculating the implicit gray market exchange rate. For example, CANTV shares closed at Bs7945/share on the Caracas bourse on February 6, 2004. That same day, CANTV ADRs closed in New York at $18.84/ADR. Each New York ADR was equal to seven shares of CANTV in Caracas. The implied gray market exchange rate was then calculated as follows: ![]() Gray Market Rate={7times Bs7945/share}over{$18.84/ADR}=Bs2952/$}. The official exchange rate on that same day was Bs1597/$. This meant that the gray market rate was quoting the bolivar approximately 46 percent weaker against the dollar than what the Venezuelan government officially declared its currency to be worth. Exhibit 1 illustrates both the official exchange rate and the gray market rate (calculated using CANTV shares) for the January 2002 to March 2004 period. The divergence between the official and gray market rates beginning in February 2003 coincided with the imposition of capital controls.

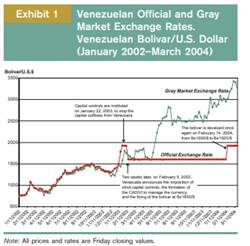

Gray Market Rate={7times Bs7945/share}over{$18.84/ADR}=Bs2952/$}. The official exchange rate on that same day was Bs1597/$. This meant that the gray market rate was quoting the bolivar approximately 46 percent weaker against the dollar than what the Venezuelan government officially declared its currency to be worth. Exhibit 1 illustrates both the official exchange rate and the gray market rate (calculated using CANTV shares) for the January 2002 to March 2004 period. The divergence between the official and gray market rates beginning in February 2003 coincided with the imposition of capital controls.

THE BLACK MARKET

A third method of obtaining hard currency by Venezuelans was through the rapidly expanding black market. The black market was, as is the case with black markets all over the world, essentially unseen and illegal. It was, however, quite sophisticated, using the services of a stockbroker or banker in Venezuela who simultaneously held U.S. dollar accounts offshore. The choice of a black market broker was a critical one; in the event of a failure to complete the transaction properly, there was no legal recourse.

If Santiago wished to purchase dollars on the black market, he would deposit bolivars in his broker’s account in Venezuela. The agreed upon black market exchange rate was determined on the day of the deposit, and usually was within a 20 percent band of the gray market rate derived from the CANTV share price. Santiago would then be given access to a dollar-denominated bank account outside of Venezuela in the agreed amount. The transaction took, on average, two business days to settle. The unofficial black market rate was Bs3300/$.

SPRING 2004 In early 2004, President Chavez had asked Venezuela’s Central Bank to give him ‘‘a little billion’’—![]() —of its $21 billion in foreign exchange reserves. Chavez argued that the money was actually the people’s, and he wished to invest some of it in the agricultural sector. The Central Bank refused. Not to be thwarted in its search for funds, the Chavez government announced on February 9, 2004, another devaluation. The bolivar was devalued 17 percent, falling in official value from Bs1600/$ to Bs1920/$ (see Exhibit 1). With all Venezuelan exports of oil being purchased in U.S. dollars, the devaluation of the bolivar meant that the country’s proceeds from oil exports grew by the same 17 percent as the devaluation itself. The Chavez government argued that the devaluation was necessary because the bolivar was ‘‘a variable that cannot be kept frozen, because it prejudices exports and pressures the balance of payments’’ according to Finance Minister

—of its $21 billion in foreign exchange reserves. Chavez argued that the money was actually the people’s, and he wished to invest some of it in the agricultural sector. The Central Bank refused. Not to be thwarted in its search for funds, the Chavez government announced on February 9, 2004, another devaluation. The bolivar was devalued 17 percent, falling in official value from Bs1600/$ to Bs1920/$ (see Exhibit 1). With all Venezuelan exports of oil being purchased in U.S. dollars, the devaluation of the bolivar meant that the country’s proceeds from oil exports grew by the same 17 percent as the devaluation itself. The Chavez government argued that the devaluation was necessary because the bolivar was ‘‘a variable that cannot be kept frozen, because it prejudices exports and pressures the balance of payments’’ according to Finance Minister ![]()

![]() . Analysts, however, pointed out that Venezuelan government actually had significant control over its balance of payments: oil was the primary export, the government maintained control over the official access to hard currency necessary for imports, and the Central Bank’s foreign exchange reserves were now over $21 billion. It’s not clear whether Mr. Chavez understands what a massive hit Venezuelans take when savings and earnings in dollar terms are cut in half in just three years. Perhaps the political-science

. Analysts, however, pointed out that Venezuelan government actually had significant control over its balance of payments: oil was the primary export, the government maintained control over the official access to hard currency necessary for imports, and the Central Bank’s foreign exchange reserves were now over $21 billion. It’s not clear whether Mr. Chavez understands what a massive hit Venezuelans take when savings and earnings in dollar terms are cut in half in just three years. Perhaps the political-science

student believes that more devalued bolivars makes everyone richer. But one unavoidable conclusion is that he recognized the devaluation as a way to pay for his Bolivarian ‘‘missions,’’ government projects that might restore his popularity long enough to allow him to survive the recall, or survive an audacious decision to squelch it. ‘‘Money Fun in the Venezuela of Hugo Chavez,’’ The Wall Street Journal (eastern edition), February 13, 2004, p. A13

TIME WAS RUNNING OUT Santiago received confirmation from CADIVI on the afternoon of March 10th that his latest application for dollars was approved and that he would receive $10,000 at the official exchange rate of Bs1920/$. Santiago attributed his good fortune to the fact that he paid a CADIVI insider an extra 500 bolivars per dollar to expedite his request. Santiago noted with a smile that ‘‘the ![]() need to make money too.’’ The noise from the street seemed to be dying with the sun. It was time for Santiago to make some decisions. None of the alternatives were

need to make money too.’’ The noise from the street seemed to be dying with the sun. It was time for Santiago to make some decisions. None of the alternatives were ![]() , but if he was to preserve his business, bolivars—at some price—had to be obtained.

, but if he was to preserve his business, bolivars—at some price—had to be obtained.

Case Questions

1. Why does a country like Venezuela impose capital controls?

2. In the case of Venezuela, what is the difference between the gray market and the black market?

3. What would you recommend that Santiago do?