Gulf Airlines challenge a global industry

Three airlines in the Gulf region are challenging European and US airlines in their most profitable business: long-haul connections. The three ‘superconnectors’, Emirates, Etihad Airways and Qatar Airways are intensively competing with each other by investing in modern aircraft and upgrading their airport hubs. Together, they have become the most disruptive force in global aviation.

Launched in 1985 in Dubai, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Emirates serves 140 destinations in 70 countries. It is the largest customer of the ultra-long-range

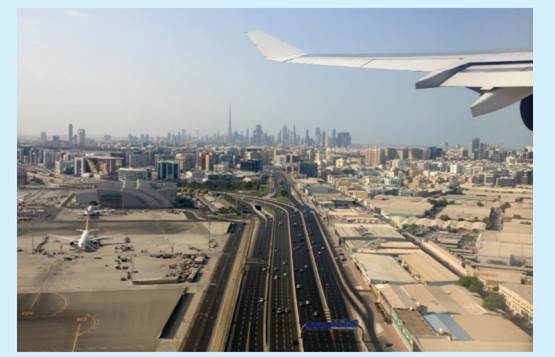

Boeing 777s and Airbus A380s. With these capable jets, any two cities in the world can be linked with one stop via Dubai. In 2016, Emirates carried 55 million passengers. Emirates makes the most of its location. Dubai International Airport (DXB) is an ideal stopping point for air traffic between Europe and Asia, and between Africa and Asia. Connecting 220 destinations, DXB handles over 40 million passengers a year, soon to be expanded to 60 million a year. Since Dubai’s own population is fewer than four million, the majority of the passengers are connecting (transit) passengers who are not from or going to Dubai.

Emirates is directly challenging traditional long-haul carriers such as British Airways (BA), Air France-KLM and Lufthansa. These established airlines fear that just like no-frills competitors squeeze their short-haul flights, Emirates can threaten their profitable long-haul business. In fact, Emirates already has more intercontinental seats than BA and Air France combined. Emirates focuses on secondary (but still sizable) cities, such as Manchester, Hamburg and Kolkata. Passengers flying, for example, from Hamburg to Sydney may not care whether they change planes at Frankfurt or Dubai, especially when Emirates flies newer and quieter planes, offers cheaper tickets and provides better amenities. One of Emirates’ open secrets of success is to fly super-sized planes – one A380 can carry 500 passengers – to reduce the cost per passenger. The savings help to undercut the fares of traditional airlines.

However, Emirates faces aggressive competition from two regional rivals that realized that geographic advantage is not a Dubai monopoly. Doha, Qatar, is only 200 miles from Dubai. Qatar Airways, founded in 1992, put in service the first next-generation Airbus, the A350-900, on the Doha to Frankfurt connection. Replacing its ageing Doha International Airport (handling 15 million passengers in 2010), Qatar opened a new international airport at Hamad in 2014 with a capacity of 29 million and a projected future capacity of 48 million. Signalling its global ambitions, Qatar Airways built up a 20% stake in IAG, British Airways’ parent, as well as 10% each in of LATAM and Cathay Pacific.

Closer to Dubai, Abu Dhabi (a fellow emirate in the UAE) launched Etihad Airways in 2003. It quickly became the fastest-growing airline in the history of commercial aviation. Only a 45-minute drive from DBX, Abu Dhabi International Airport had a capacity of 20 million in 2012 and plans to expand to 40 million. Etihad Airways developed its business by partnering with smaller European airlines facing liquidity difficulties, which it developed as feeder airlines for its global network. Thus Etihad acquired a 30% stake in (the now bankrupt) Air Berlin of Germany, 49% in Italian Alitalia and 49% in Air Serbia.

All three airlines from the Gulf are heavily investing in marketing and branding in Europe. Football fans tend to know ‘the Emirates’ (the home of Arsenal Football Club) and ‘the Etihad’ (formerly City of Manchester Stadium). Emirates also sponsors a veritable portfolio of AC Milan, Real Madrid, Paris Saint-Germain, Hamburger SV and Olympiacos. Qatar Airways is aiming very high with its deal with Barcelona FC, while Etihad is looking further afield, sponsoring Melbourne FC and New York City FC.

European airlines have been fighting back with their own aggressive pricing and new offerings, but also lobby to restrict the Gulf operators in Europe because of the ‘unfair’ subsidies their new competitors allegedly receive in the form of cheap fuel and low airport fees. Emirates responds that it pays slightly more for fuel at home (DXB) than abroad, because of the lack of refining capacity in the Gulf. Moreover, since Dubai provides few social services to expatriates, Emirates spends $400 million a year to provide accommodation, health care and schools for its staff – a huge expense that rivals do not have to cough up. In 2015, US airlines felt the pinch too and demanded that the USA take action, claiming that the three received hidden aid worth $42 billion, mainly in the form of interest-free loans and guarantees. Also the political instability in the Gulf region and restrictions put in place by the US authorities, supposedly aimed at reducing terrorism risks, hit the three superconnectors.

However, competitors are not standing still. Turkish Airlines is investing in expanding its network, while new long distance carriers spring up across Asia. European, Asian and US airlines are upgrading their facilities and partnerships. Will there be enough air traffic for all of them? Some analysts speculate that there may only be two survivors of the ‘superconnectors’. Who will be the survivors of this intensive competition?